[The Insignia Pin is an original allegorical fable intended for our times that I’m offering to you in weekly-serial form.

The Insignia Pin is an epistolary novel - composed as though the characters themselves are writing it.

This is Part Nine. Please read Part One through Eight to follow this weekly serial post… and thank you for sharing with others.

Please note: The Insignia Pin is rated PG-13 for coarse language, drugs, war violence, and teen sexuality.]

Frank, 1969

We woke to mortar fire and Sergeant Akers screaming out, “Hold your position!” But everyone ran to save their own lives. I found Paul huddled down in the corner of the trench’s zigzag, paralyzed and gripping his rifle tightly. I shoved him and shouted we had to get the hell out of there.

I helped him climb the trench wall and practically carried him further on. By then there was so much ordinance and explosions, it was total chaos. One huge swoosh, and I flew backwards like a puff of cotton into the air and then set gently back down. I got up without a scratch on me.

But where was Paul? He’d been climbing up about ten feet to my left, so I called out to him through clouds of dirt and dust.

His torso was where he'd been climbing – up against the trench wall. Some part of me goes back to the sight of this in my dreams, and I’m usually trying to locate his head, which had come clear off.

I was helping to bury Paul twenty-four hours after he helped me bury Andy. I wrote a note to his mother that night.

I was convinced I'd be next and didn’t want anything to do with anyone. After Wylie Breckinridge’s execution, meeting Paul and Andy had brought me back to myself, but with them going out like that, I closed up completely and turned inward.

I thought we’d be fighting people we could see. Being shot at, bombed, gassed, or otherwise maimed without seeing your enemy was a terrific shock.

Shelling and patrols eased up for a brief time. Several men had already started digging from three a.m. until noon for a couple of days to build a bunker. I became desperate to dig down twenty-five feet below ground with them. Somebody said that was the only level safe from the bombardments. Trench level and above was a place of slaughter.

There were only pauses to smoke. There just wasn’t anything left you’d want to talk about. Strangely, Akers tolerated these diggings if we stayed “within regulation.” Who knew what they were? We took to our finished bunker like moles, and it brought us false comfort.

I was glad not to have to look at Akers any more than I had to. He’d held no field ceremonies for Andy or Paul like other NCOs did. Our Holy Joe told us Akers said Taps would no longer be blown because it hurt morale. All anybody else in our regiment ever heard about the fates of my friends was they were “na-pooed” - Brit slang from listening to French soldiers, meaning they “were no more.” It was as though they’d disappeared.

When things weren't hot we were allowed to rest. We ate ‘goldfish’ – doughboy slang for canned salmon – and drank cold coffee. If Akers allowed a fire long enough for the little oven we’d rigged, some of us would toss together “monkey meat” or “slum,” a hodgepodge of anything edible. It was not beyond imagination that this might include rat meat. I sometimes ate only hardtack to get over my ailing stomach.

Our bedding of fresh hay spoiled easy. Lice were the bane of our existence; nothing could be done about the bloodsuckers. The doctors believed the cooties gave soldiers trench fever, so large, heated water trucks were sent lumbering along what passed for roads, and we’d have to climb out of our diggings, tug off our clothes, and stand stark naked while our uniforms were steamed. It was a rare sight, groups of naked boys gripping their rifles tightly during this operation. After we finished this steaming, we’d put our wet clothes back on and crawl back below ground. A single night would bring all the cooties back, and we’d be scratching again by morning. It seemed complete madness.

Akers expected “three-on-three” in the trenches at all times. He’d split us between rest underground and sentry duty on four-hour shifts. The Huns were forever moving around, and we were seldom sure whether we were losing or gaining ground. Sometimes they got close enough to where we’d hear them talking.

One morning, I heard some shouting and raised up my trench periscope. Four Huns were standing in full view just fifty yards away. It was the first time I’d actually seen the enemy in the flesh. Along with me, several other sentries sidled up their ladders, and we aimed our rifles at these men as they shouted out in English about being tired of war and wanting to surrender.

Akers suddenly shot up my ladder right behind me screaming, “Shoot them, McCaffrey, shoot!”

What I saw before me were unarmed men trying to surrender.

Akers climbed higher, breathing down my neck, “Fire that rifle, McCaffrey!!”

He tugged it out of my hands, rested the barrel on my shoulder, and shot two of them in cold blood – just bang, bang. They fell like stones.

A machine gun came into full view right behind them and opened fire on us. Akers and I fell backwards off the ladder and into the trench. Two of our sentries fell back too, dead.

Akers stood up, brushed off, snaked in between other men, and pulled his pistol out of his holster. He shoved me up hard against the wall of the trench, jabbed the barrel into my nostril and cocked back the hammer.

“Hanging n——s didn’t make you man enough, so I’m going to blow your brains out, McCaffrey.”

“Go ahead, you goddamn maniac,” I sneered at him.

A couple of fellows pulled us apart. I dusted myself off and spit harsh onto the ground. I stayed eye-to-eye with him and swore to myself I’d kill him if ever I had the opportunity. I never felt such hate before. He just holstered his pistol, turned and walked away.

From then on, Akers did all he could to get me killed. This started during “the big show,” a section push, when he sent me on a whole bunch of runs through communications trenches. I had to carry messages ten kilometers back to headquarters and between various platoon sergeants. I also had to scout because anybody carrying communiques would know best how the puzzle of trenches was laid out and where the enemy might have infiltrated. All of these assignments made me a highly desirable target.

The new field telephone lines got blown up no matter how deep we buried the cables. Everything depended on regimental runners like me, and our lives weren’t worth a damn. Akers saw me as sniper’s meat, and I knew surviving these runs would be the only way I’d ever beat him.

While I was out, my heart would pound so hard I’d get faint trying not to think about somebody zeroing in on me. It might’ve been easier to carry as little as possible, but out of uniform, I risked being shot by friendly fire. Besides, communication trenches edged through No Man’s Land between the German and Allied Lines. Nobody in their right mind would want to get stuck there without a pack. Every run meant fifty pounds of gear - tin hat, haversack, rations, knife, grenade belt, gas mask, canteen, shaving kit, huckaback, extra ammunition, and my weapons, an Enfield rifle, bayonet, and my Colt Model 1903 Pocket Hammerless.

That’s the same pistol you took from me, son - and Sam, you don’t have a goddamn right to it. I want it buried with me.

I was on a run when our bunker was bombed and three fellows died of suffocation. The platoon sergeant split the rest of us up, and I was sent to sleep along the trench wall on a length of board. That’s how bad Akers had it in for me. I woke to catch a glimpse of two rats in a tug o’ war over a man’s hand. If the sun ever peeked through, flies and ants joined on human flesh. Maggots ran freely everywhere you sat. During a lull, black crows sat in burnt-out shrubbery or trees surrounding us. Crows will pick at any kind of carrion. Sometimes it’d get quiet except for the crows, and you felt like nothing more than a living feast awaiting Nature’s decomposers.

Everybody could feel something big coming. We soon got news we Doughboys would challenge the salient the French hadn’t been able to move one inch. This was a bulge the enemy had made in our lines. No more runs for me - Akers knew this was the better way. I’d get sent over the top into the slaughter like anybody else.

A few hours later, a series of whistles signaled to form up. The division commander’s whistle sounded first – same whistle as the London police. Loud as hell, and you could hear it a mile off.

Then the platoon sergeant screamed out, “Fix bayonets!”

We stood up, weapons ready. No surprise to any of it at all - the German machine gun fire rose to fever pitch above our heads. Everyone knew we were going to climb up and step into that meat grinder in a few seconds.

The trench officers’ thunder whistles sounded next, and we made ready to charge the ladders or climb footholds set into the walls. Now the fire was even heavier, and you could sense the wall of death above you. Men barfed and pissed or shit their pants.

Thunder whistles sounded a second time, and we each ran up and out behind one another into No Man’s Land. Muzzles of German rifles flashed from only a hundred yards away. Bullets swarmed like mad bees, and shells exploded dirt and heat trying to tear you to pieces.

We ran full steam at those German trenches, yelling at the top of our lungs, our own guns blazing, not even bothering to aim. We were going to die or not, that’s all we knew.

A storm of hate and terror shot out from us because that’s what war does, brings out the worst in men caught in the worst of life. I concluded the ideal man was built here, in battle, Sam, in hate, and not in the Christian image my mother wanted for me. This is how the violence grew inside me after I got home. This is what we learned there. Gentleness is weak; sympathy is cowardice; compassion is womanly. Kill or be killed.

We were just boys, pushed out there by politicians, generals, and the vicious men like Akers who did their dirty work. Behind them, the American voter, who couldn’t give a rat’s ass what it really meant to wave a flag.

Whoever among us didn’t charge risked being shot by Akers or any other leader. I’m telling you right here and now I saw him murder a man cowering in a trench. The only way back to safety was if the company bugler sounded retreat which was never going to happen. Combat fighting is utter desperation.

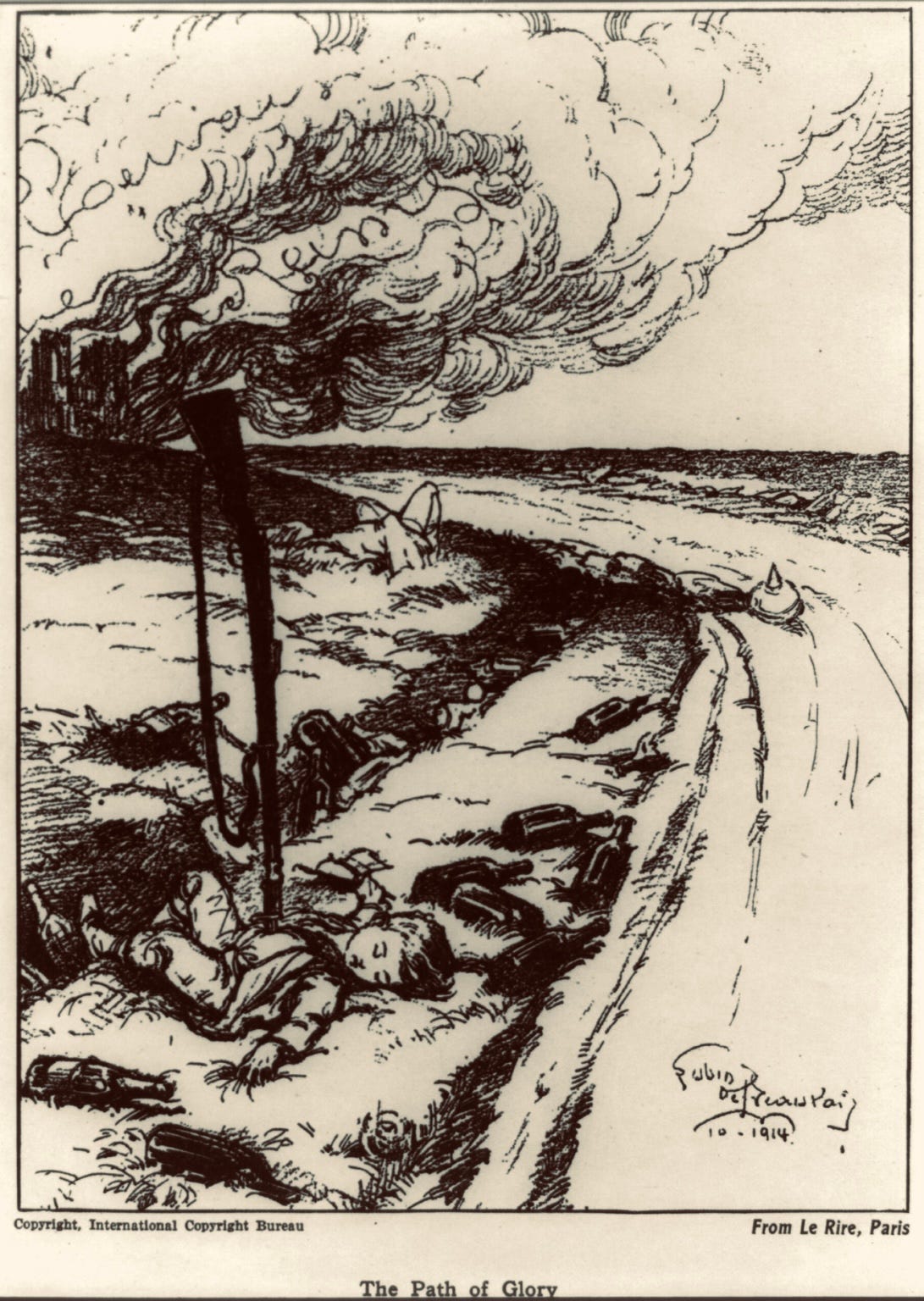

This was what it really meant for me to become a Red Devil. Maybe we gained a few yards of ground. Maybe we ended up swallowed by the ground itself. I survived the first assault only to have to go through the same thing three times in a row – charge, resist, retreat; charge, resist, retreat, and again. German machine guns cut men in two right in front of me every time. Our generals hadn’t any more sense than the French about these futile frontal assaults.

I have somehow lived to this late day in life with my voice too slurred by this stroke to speak this tale, so I am instead writing it down here to keep the memory alive for you and Oscar and my grandsons and all generations. I am telling the absolute truth about what we went through.

Even though our company wasn’t attached directly to the Machine Gun Battalion, Akers got hold of a new Browning Automatic Rifle or BAR. Small framed as I am, he naturally assigned this weapon to me. The BAR was fifteen pounds heavier than my Enfield and made me an instant target.

I carried that gun during the Battle of Saint Miheal when we were sent north to join two platoons in attacking a tiny village called Vieville-en-Haye. We were supposed to help push Germans off the French supply lines. I’d just had my eighteenth birthday and was patrolling alongside about seventy other boys.

Akers got himself in front for the guts and glory like he was the one leading us. What a farce. We began moving in small groups staggered behind Renault FT tanks led by him. I suspect he thought he’d be safer inside one.

The AEF didn’t have much in the way of tanks, so those French machines felt important. We hugged them close, and they moved at about the same pace as our walking. Every house and building we passed was already riddled and blackened with soot. As we entered the little village, I saw the church steeple with so many holes in it, I could see the sun on the other side through its belfry.

When we got to the town center, Alpine mountain guns surprised us from the right and machine gun fire came directly at us. We were being flanked.

Then I caught sight of something I never thought I’d live to see. The tank Akers and two French officers sat inside suddenly blew sky high. I gaped at the smoking hull and Akers deformed head bobbing around inside black smoke.

If there was a God in Heaven, I knew He’d helped me right then by taking this man away. Otherwise, he’d have surely killed me.

“Move forward!” the shout came.

Smoke and machine gun fire mixed with the Puteaux cannons of the French tanks. The platoon sergeant shouted for us to don gas masks. But the Huns didn’t waste gas on us that day, and scouts ran back to say they were already moving out to the northeast.

The sergeant ordered me and two soldiers to get to the ridge, and “catch them as they run!” I checked the other fellows were still behind me as we spun around a street corner. Then I looked forward at two Germans running right at me with their hands up and rifles slung over their shoulders. I shot them both dead with the BAR before thinking.

We scrambled up on the ridge and saw two hundred more running. I fired and several fell but I couldn’t be sure what was my doing. Shells started bursting above us, and we hightailed back. That’s when the bugle finally sounded.

Somebody yelled, “Retreat! Take cover along the western perimeter!”

I scuttled down into the basement of a row house. Nobody came in behind me. I had the shakes so bad, it took five minutes sitting in the dark before I could strike a match.

A mother in a pretty blue dress and three little kids lay there, two little girls and a little boy, not more than six or seven years old, all face up, all dead.

I climbed up to peer through broken brick. Dust hit my eyes, and I knew I would have to stay put.

I went over and lit another match. I just couldn’t get out of my mind that I’d been firing the BAR from the ridge along this general direction. It still tell myself they'd probably been lying there for days. I just couldn’t feel certain it wasn’t me who killed them.

The Germans shelled us for hours, but they never did come back, so the battle was considered a great American victory. There were only thirty of us still alive, and we still had to get back from behind German lines.

A corporal decided we should head south. At another ridge we saw more Huns than we could count about a hundred yards ahead and directly in our path home. We’d followed their retreat, something we hadn't meant to do.

A buzzing sound came overhead, and every fellow looked up. Some of the enemy looked up too and started running. Others turned their rifles toward the sky, shot a few rounds, and then also took off.

Four airplanes soared overhead - Americans flying Spad biplanes from Third Pursuit. The ground ahead of us tore apart as they strafed. It seemed like they were marking the road back for us. The corporal blew his thunder whistle, and we all ran forward.

About then, the planes banked to the left to circle back. We began running faster.

How could they know who we were? They couldn't.

Two fellows ahead of me shed their packs and rifles, and I did the same. Those four dots got bigger as the airborne gunners fixed their sights.

I stumbled as they swooped, ground parting around me as rounds hit earth. The two men in front of me fell and didn’t get up.

Life was all I had left. My breath was gone. About then, I realized I was out of uniform and didn’t even know the password to our own lines. I just kept running.

Twelve of us dived back into the French trenches that morning, the only men from our platoon to survive.

I peered up at the sky, enraged, as the Spads roared off. Two French officers argued about what to do with us. Eventually, we were temporarily blended into other units.

From there, we went right back to how it was. I helped dig new positions with men I didn’t know and didn’t want to know. I set sandbags and barbed wire, crawled around watery trenches, fought rats, and stood sentry duty.

This is how I survived the Great War.

By telling you about it, I wish you to understand the impossibility and unlikelihood you would’ve ever been born.

Visit any military cemetery near the Belgian border and check the ages of the boys beneath those stones. They’re mostly kids. Not too many officers like Akers.

The cemeteries were for those who got tended properly. Most of the bodies I helped bury were left in shallow, unmarked graves during lulls in the fight. Their wooden crosses and Stars of David are now long gone.

It is in those times that my own attraction to oblivion began.

Even in hard times, French soldiers got a half-bottle of wine a day, and the British had steady rum rations. But old Pershing banned whiskey and rum for the Doughboys. This never stopped us, of course. French wine was everywhere, and we had no trouble finding schnapps and vermouth too.

I carried the same little flask of liquid courage many boys kept over our hearts, dual-purpose body armor and fear stopper. With a few shots of schnaaps, I might bang my ankle or foot on a run and not feel a thing.

One morning, I came charging back into camp starving hungry after two night runs. I was probably a little drunk when I grabbed and chewed a chunk of bacon still sizzling in a pan over the fire. Bacon was always a real prize of a meal, and I grabbed blindly for the smell and taste, not thinking at all.

Somebody yelled, “Hey! Stop!! Don’t eat that!” but it was too late. I knew what I’d done and spat it out.

The whole camp had been gassed. Anything cooking over the fire too.

Thirty minutes later, my lungs filled with fluid, and I vomited and lost my voice. The most painful cough you can imagine wracked my body. My throat closed and I began to suffocate. Pain so intense I couldn’t swallow.

I don’t remember being evacuated, but I was told we got lost driving to Dijon. I vaguely recall being dropped off in agony at Vichy Base Hospital.

I’d eaten mustard gas as opposed to chlorine or phosgene, which the Germans also used. Mustard doesn't just affect you by what you breathe. It falls in tiny particles and lingers in puddles and in the dust. It gets into your clothing. You might be standing around when some horse shook his mane, and suddenly everyone nearby starts ripping off their uniforms and running full speed to the “bath truck” to scrub down with soap and water. You only have a few minutes.

What mustard does is make blisters. After I swallowed the bacon, they started popping out on my tongue and all the way down my throat and esophagus. I also inhaled it too, and this brought blisters up inside my lungs.

It was mustard, not Sergeant Akers, that nearly killed me.

I lay there in a cot in Vichy, so overcome by pain that the nurses strapped me down. Here was this hardscrabble country boy, now a combat soldier, brought so low by two spit-out pieces of bacon as to beg to meet his Maker.

Other boys around me had it much worse, especially those who’d gotten it into their eyes - swelled shut and caked over with puss. The nurses had to restrain their hands to keep them from dabbing at the pain and intense itching behind their bandages.

The mustard gas wards were strange places where nurses and doctors always kept themselves safe behind protective garb. You’d never see anyone where you might be able to recognize him or her later. They’d whisper to you and be difficult to understand, but you’re too exhausted and hurt to ask them to repeat themselves. I do recollect a certain French nurse who had a voice that meant a lot to me, but I’ll never know who she was.

The ward echoed with moaning and retching. They’d pour bicarbonate of soda and opiated cough syrup into our throats, but I begged for morphine. They simply refused. One finally told me that he was afraid it would suppress my breathing and kill me. I informed him this would be just fine.

I developed the gas fright, where you become unreasonably nervous about getting gassed again. Due to the way I’d been exposed, the nurses couldn’t get me to eat much, and I peeled off considerable weight. I gradually became so weak I could no longer walk.

I spent three months at Vichy. The Great War had ended, and I was evacuated via hospital ship and train all the way to Fort Whipple in Prescott, Arizona. The dryness of the climate was thought to help damaged lungs, and the military hospital there was strictly for treatment of mustard gas poisoning.

The hospital was completely white, floor, walls, and ceiling on all six floors with about a thousand patients. I came there weak as a kitten, depressed and withdrawn, and had pretty much given up on life. I ate mostly saltine crackers. They put me in a wheelchair, but I wouldn’t roll it. They contacted Mother and Pearl, but they lacked funds to come. I was glad because I couldn't stand to have either one of them see me.

The medical people encouraged families to write their loved ones, and both of them did, but I only wrote back once when one the nurses pushed me to dictate to them.

I had given up on life, I admit.