[The Insignia Pin is an original allegorical fable intended for our times that I’m offering to you in weekly-serial form.

The Insignia Pin is an epistolary novel - composed as though the characters themselves are writing it.

This is Part Seven. Please read Part One through Six to follow this weekly serial post… and thank you for sharing with others.

Please note: The Insignia Pin is rated PG-13 for coarse language, drugs, war violence, and teen sexuality.]

Frank, 1969

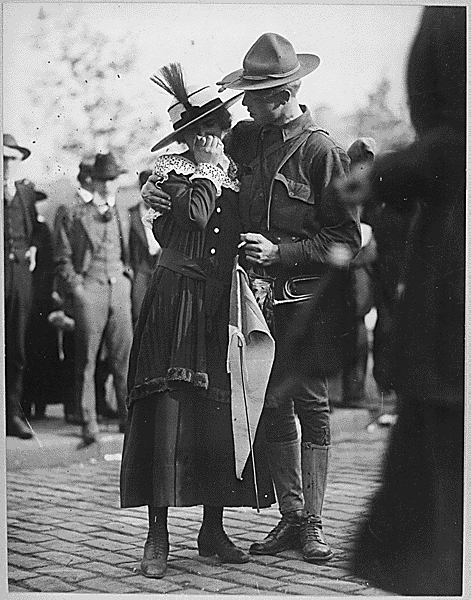

On April 24, 1918, I was shipped out. I was seventeen years old and no longer a boy. I was, by any account, a soldier trained to kill who’d follow orders to do so, and I saw myself even more in this way by participating in the hanging of Wylie Breckinridge. This idea that I could be made go against my own moral code brought me many nightmares. I’d see Wylie standing in front of me, begging me to shoot him. I’d aim my rifle at his forehead but then be unable to pull the trigger. In one dream, I pulled the trigger, but then my rifle jammed. I felt responsible for Wylie’s death despite what any chaplain tried to tell me.

By helping execute a man, I’d been made older than my years and certainly older than the other fellows marching onto the Leviathan at New York Harbor. Despite being hardly visible among the thirteen thousand other men from the Fifth Division of the American Expeditionary Force, otherwise known as the "AEF," I now knew myself as someone sullied, different, and alien.

Several thousand among these men, including me, arrived at the docks by train. Once mustered, we stood stiff as boards in endless rows for our first inspection, while they passed out Red Diamond patches for us to sew on our sleeves. We were told none of us had yet earned the German nickname for these patches - die rote teufe - the Red Devils. But inside myself, I begged to differ.

Out the corner of my eye I saw Sergeant Akers for the first time speaking with senior officers at the front of our formation. I’d never hated anyone before in my life – except, of course, my father - but I hated Akers far worse. I was outraged he’d been appointed our Company NCO (non-commissioned officer). But with two hundred other soldiers deployed under him in Eleventh Infantry, some comfort could be found in not having to see his ugly face so often.

Leviathan was a German-built luxury ship called Vaterland before the U.S government seized and refitted her. She spanned a thousand feet long and looked unworldly with her "grey and dazzle white" camouflage. Carrying fifty pounds of gear, a soldier might nearly fall over backwards staring up at her smokestacks while waiting on her steep gangplank.

A Bluejacket guard shoved me from behind, which immediately irritated me. He was soon offering us genuine pre-rolled French cigarettes he’d picked up on his last trip across. He enjoyed our ignorance, and before we could ask anything, began explaining how Leviathan's paint job made us harder to target. He put a lot of emphasis on “us.”

Given how I was feeling, I pushed myself to try to fit in and accepted a cigarette. But I’d never smoked before and fell into an impressive coughing fit.

“Easy there, Army,” he said slapping my back, making it worse. “These smokes are for Navy men. Take my advice and eat light. We’ll be making twenty-two knots all the way to France.”

He then pushed past me again, jostling me, and yelling, “Make way, make way there!” like he was a commander or something.

The meals on Leviathan were bigger than any I’d ever seen. For a boy who grew up hungry, I thought to eat all I could while I could. After all, I’d never been on the ocean and knew nothing of seasickness. It wasn’t too long before I was fighting for space at the railing next to some petty officer screaming at me for messing his deck.

There were twenty ships along with us including George Washington, a small transport, the Warrington, a destroyer, and several sub-chasers. The ships fanned out across the entire horizon, and we watched them zigzag - standard procedure in U-boat waters.

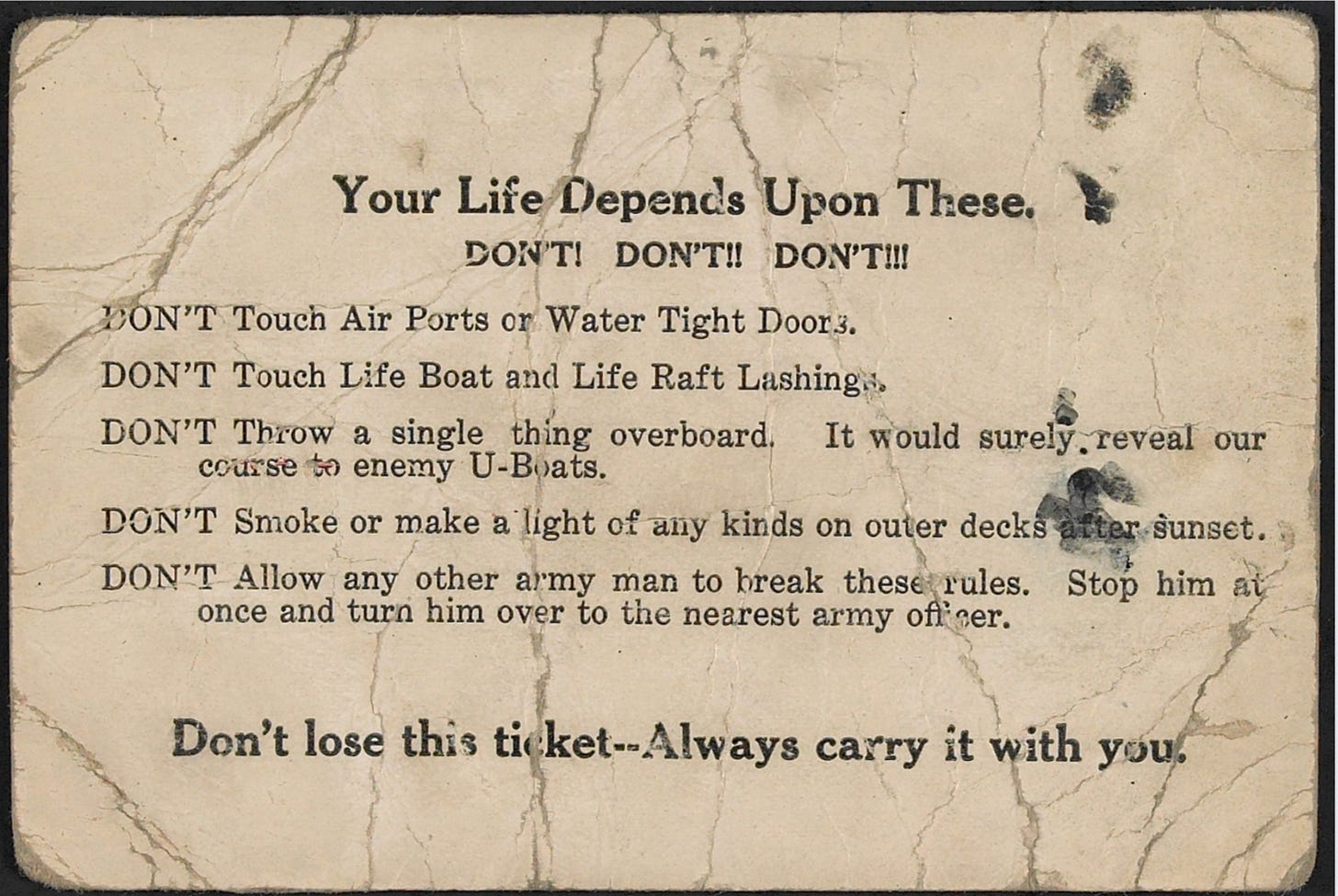

Our greatest danger - being blown to bits - was something Bluecoat had enjoyed mentioning. We’d be most at risk where the convoys came together in Bay of Biscay on the journey into Brest harbor.

He and his fellows drilled every day at six-inch guns bolted to every side of the ship. The guns were loud as hell, and we were impressed watching the Navy boys work alongside Warrington and the sub-chasers to range for imaginary U-boats. But I couldn’t stop wondering, would those guns thwart the Germans trying to launch a real torpedo at us? I had my doubts.

At night, when the seas got choppy, my stomach would churn from the jitters while I lay in a berth so tight you’d have to squeeze your arms together just to roll over. It was one thing to read about U-boats sitting with Uncle Henry but something else entirely trying to shake the notion we might be in their very sights then and there.

Soon a rumor began circulating as to how we didn’t have a strong enough convoy, and we’d all go down in the middle of the Atlantic before making it to France.

Drowning - what a way to die with your lungs filled so you can't breathe! Even fifty years later, I hate to admit how afraid I was. I was raised to the idea that if you’re any kind of man, you push it all down. You can’t let it show because if you break, the fear will take other fellows too. Then, we’re all doomed.

To challenge my inner cowardice, I decided to step forward as a volunteer nighttime relief spotter. This proved a very eerie business. I moved my binoculars back and forth for hours at a time following searchlights as sweeping across the waters. The work was very dull, and I’d get so sleepy, somebody could be looking through a periscope right at me, and I’d never know a thing until the torpedo hit us. Such thoughts would jolt me back into focus. It wasn’t any more reassuring when somebody else took over - I didn’t trust they’d remain any more awake.

Yes, I tried calming myself remembering the sub-chasers in our convoy had new “hydrophones” until Bluejacket mentioned U-boat captains already knew how to sneak past these contraptions easily. He seemed to love keeping us edgy, and who could blame him? Such fears were any sailor’s life working on the transports. We’d eventually be safe on shore, but not he.

Bluejacket said U-boat captains always saved their torpedoes for bigger quarry like our Leviathan. We already knew them to be a ruthless and brutal bunch. They’d sunk hospital ships and machine-gunned survivors climbing into lifeboats.

Being drilled every day in fire preparation and abandoning ship only further jangled my nerves. Few of us slept. Maybe the good side of seasickness and U-boat fears was they kept us distracted. Being on a voyage to France to fight in a war was glossed over, and few of us talked about it. We were more concerned about making it there. We wanted off the damned boat, and I was among many very relieved after passing through Bay of Biscay on May Day, 1918 without seeing any trouble.

We disembarked at Brest, and then marched several miles to the Pontanezen Barracks. This new home made the tight berths we’d left behind on ship seem desirable. Pontanezen Barracks were named Le Camp de Repos by Napoleon’s men. The irony of the name was that any decent soldier would prefer fighting to staying in such a hole.

Rain started the moment we arrived, and I don’t believe it stopped for more than a single hour all the time I was in France. Our tents leaked, our gear got soaked, and there were no wooden floors. The better tents had gone to the front lines.

None of this mattered that much because Akers kept ordering us outside in the rain to dig latrines. Somebody noted how our daily lives had become just water, piss, and shit. The lanes around our barracks got so deep with this vile mixture, I’d find myself searching for grass to walk on constantly but eventually sink into the morass anyway. It made no difference. Each of us gradually surrendered inside ourselves to constantly feeling cold, wet, muddy, and filthy.

When we weren't digging, Akers kept on us with constant drilling, loading trucks, or combat training. At day’s end, we slept like the dead on flimsy cots made of kindling and chicken wire nailed together.

It rained so hard and long that the light never seemed to rise above dusk. A couple of weeks into this routine of exhaustion and shit, we felt overjoyed to be mustered with all our gear to finally march out toward the trains and the war. None of us knew one another very well yet, and of course, we knew nothing of what lay ahead. We were just very glad to leave behind where we’d been.

As we marched into the countryside, we began passing hordes of refugees, including countless French peasants fleeing the German Spring Offensive. So many rickety old wagons struggled by us tightly crowded with women and kids sitting on large cloth bags stuffed with belongings and beat-up furniture. What struck me was how few horses there were. All these worn-out old grandpas were tugging carts and wagons holding people or pushing wheelbarrows stacked high with clothes, a few wilted vegetables, and household items. Worn-out grandmas too. It was quite a time before I realized there were hardly any young men left, and most of the horses had been requisitioned, looted, or eaten.

So many faces had the hollow look of starvation. The Germans were closing in on Paris, and they’d pillaged what little they had left. The big national hero, French General Duchene, permitted his soldiers to loot any food, fuel, and metal they needed from France’s own people. This man believed only in attack and his strategic failures left everyone in the countryside defenseless. Even his own soldiers mutinied. The French people were victimized by every army in the Great War, especially their own.

But here we Yanks were just happy to be finally moving – healthy, rosy cheeked and carefree with our patriotism and sense of superiority. All around us ran swarms of little kids with narrow, dirty faces calling out “Chocolat! Chocolat!,” pulling on our pockets, and begging for our Army-issued Hershey bars. We felt special – even unusual and a bit awkward - the American boys from the greatest nation on earth, crunching over miles of rubble that had once been their homes.

It wasn’t long before we lost our smiles completely. Soon, just about everywhere we turned our heads, we saw field after field of crosses. We found ourselves vastly outnumbered by the buried dead. When I think back to all the children chasing us, and trying to dismiss or push them away, I still feel the shame I felt at having given them so little after seeing the graves of their brothers and sisters, fathers and mothers, grandfathers and grandmothers. It was as though we came around a corner, and the world had come to an end and left only children desperate for chocolate. I couldn’t even eat it.

I didn’t want any of my fellows to know how all this was affecting me. Sure, I saw some tears in a few eyes, but none of us wanted to get emotional. No man spoke about any of what we’d seen when we stopped to rest and eat. But our bunch of rowdy loudmouths had become very quiet by then.

I think many of us had begun wondering if we’d be “man enough” to keep moving toward whatever so many people were desperately moving away from. The front lines. The war itself. Would any of us be buried out here ourselves among all these graves?

We finally rendezvoused with staggering numbers of other soldiers, which seemed to shake us out of such bleak thoughts. Each of us struggled to hoist our gear and squeeze into the tiny compartments of the troop train.

I was fortunate to sit with two of my Pontanezen Barracks tent mates, Andy from Iowa (I can’t for the life of me recall his last name) and Paul Daniels from New York.

Andy called me "sir" until I told him cut it out. He was so religious, he thought it a sin to play cards until I coaxed him into learning Gin Rummy. It turned out nonetheless that he had a mischievous side.

Paul played cards too, here and there but considered himself too sophisticated to make it a regular pastime. He'd taken to packing and smoking a pipe at the tender age of twenty-two. He had wavy black hair and spoke fluent French, and Andy and I thought him a sort of East Coast dandy. I think Andy would’ve liked to take him down a notch.

Our train was taking us to Beau Desert, France with other sections of Fifth Division. Once we got more settled, Paul began talking ad nauseum about some French novel he’d read before leaving New York. This was very tedious, but we pretended to be interested while watching the countryside roll by. I think Paul got impatient with our divided attention and so set us up to learn Piquet using a few of the French coins we’d been issued at a centime a hand.

"I thought you’d no use for cards," said Andy with a wink toward me.

"This is a two-player game, so each of us takes turns sitting out," said Paul ignoring him.

Andy was no good, and Paul enjoyed cleaning him out, which was not lost on Andy. However, when Paul and I faced off, I got two carte blanche in one sitting, and he stood right up at his seat to declare, "this is completely impossible!"

The facts of my cards annoyed him to no end, and I finally told him he was one sore loser and might just instead be proud because he’d taught me how to play pretty well.

Paul sat back down and puffed his pipe overmuch and griped that I smelled very bad, and this was why he had to keep smoking.

Andy leaned back and shook his head.

"Well, Paul,” he remarked lazily, “it's pretty clear to anybody nearby that the threat of fire, smoke, and gas emanating from your own body will turn any hand you're dealt sour."

Paul looked at Andy like he was seeing him for the very first time. His mouth fell open without a word, and then he fell into a kind of hysterics at being so one-upped. Andy's remark got all of us in a stitch, and from there, we were made fast friends.

At Beau Desert, they took us into special training for mountain warfare. Our days were sixteen hours long. Akers aimed to abide absolutely by General Gordon’s orders that we wear gas masks during every single exercise. I hated the mask and kept losing my wind trying to breathe through the canisters. The gear made me sweat like a pig too, and I caught Akers' wrath trying to take off my pack to shimmy under a round of barbed wire. He often cancelled everybody’s liberty because nobody was “up to snuff.” We didn’t have energy to go anywhere anyway.

I guess we seemed a boastful bunch to our French small arms instructors because many of us had shot and hunted before. They responded roughly to our overconfidence when we were with them on the range, punching us in the shoulders while we aimed, shoving men around and into each other, and repeatedly yelling at us about wasting ammunition. My marksmanship actually got better under the pressure, and I earned the circle patch of a sharpshooter.

When my French instructor spotted how I'd sewn it onto my sleeve, he got all disgusted and said, “Felicitations, vous ferez une bonne cible.” I’d made myself a good target. I clipped it off my sleeve that same evening.

We eventually had our orders in hand and began our journey toward combat. On the train north, Andy, Paul, and me tried to be lively with jokes, cards, and smoking like chimneys along with the rest of about five hundred of our brothers in arms. We were being sent out to reinforce the French in the Anould Sector of the Vosges Mountains near Alsace – the roughest terrain of the Western Front.

I didn't see a soul actually sleeping on the long train ride.

At Chaumont, we pulled into Fifth Train Headquarters and formed up into regiments for inspection by General Pershing himself. We were warned that if any soldier looked in the General’s direction, he’d be standing at attention at the officers’ barracks for the next day and night. I marched right past the man but never laid eyes on him.

Following this pomp, they set us free to stroll around for a few hours. Andy and I went together, but Paul had his own ideas. We found the yards packed with engineers and laborers building lines of new train cars. Hundreds of wagons overloaded with supplies were being unloaded into gigantic open warehouses. Automobiles and trucks in endless lines created huge clouds of exhaust.

Andy and I came up close on a railcar mounted with fourteen-inch guns. Here was a huge monster that could toss a fourteen-hundred-pound shell twenty miles. We knew the Germans had guns like ours, and I felt a twinge in my chest considering being underneath an exchange between such giants.

Andy and I bragged to Paul about all we’d seen after we loaded aboard our next train and began tracing a path along the Moselle River. But Paul stopped us cold by giving us details of his activities with a French prostitute that afternoon. I was quite innocent and got embarrassed. I mentioned that it seemed a shame a woman would allow herself to be so compromised. Andy claimed all the sin lay with the man.

"Mary Magdalene was cut from the same cloth," he pointed out, "and she consorted with Jesus himself."

Paul laughed and toyed with his pipe while we two bumpkins held court about his eternal damnation.

It was at Fresse-sur-Moselle that we came close to the action for the first time. Fresh blackened spires of wooden framing met us alongside mountains of broken lathe, plaster, and brick, abandoned paintings, pictures, clocks, cups and plates, papers, furniture, and children’s dolls. I kept seeing dolls everywhere I looked, and I’ll never know why. All the debris was too heavy or worthless to be carted or carried by helpless people now displaced and starving. What buildings still stood in the small town were crumbling facades.

We got out of our train car for a short time to look it all over. Moselle was crawling with French and American soldiers, waiting to head into the mountains. Soldiers passing through were the only people with any money or food left, and local people surrounded us, pushing trinkets or meager crafts at our faces or begging – too hungry to care who they blocked or where they happened to be standing.

A French military policeman got very rough with an old man standing in the street blocking a mule-drawn wagon. Andy walked over to him and shouted at him. I was ready to pounce him too, but Paul said we risked creating an international incident. The old man got up from where he'd fallen in the mud and shuffled away.

A girl with long black hair tied into a calico scarf ran right up to me. In my memory, she remains the most beautiful girl I’ve ever seen. She pushed out a basket of eggs, looking hopeful, nodding and smiling.

Paul asked her questions in French, and she answered, although Andy and I hadn’t a clue what she said and just stood there gawking. She soon pushed the basket at us again. Paul asked more questions which I think got her hopeful we'd buy some eggs. She told us she’d come up into the mountains a few months earlier to care for her grandmother, leaving mother and sister behind in Paris. He told us he was asking her about her father and whether she had brothers, and we both told him to stop prying.

“Ils ont été mangés par la Gare de l'Est,” she said as she lowered her eyes.

“The East Station ate them.” This was the East Station in Paris where French soldiers often said goodbye forever to their wives and kids and sweethearts. She'd lost all the men in her family there.

Irritated with Paul for digging this out of the poor girl, Andy and I bought all her eggs before hurrying onto the mountain train. We’d no idea what coins were what and just handed her a bunch. She was amazed by this and became tearful.

There we were with all our gear back on the train and a bunch of eggs, wrestling for the window to wave goodbye to her. After we pulled away, Andy scolded Paul for “making pretty girls cry.”

The track we found ourselves on was narrow gauge, and the train car was much more cramped. The steep grade into the Vosges disappeared beneath us as we began to cross over several splintered bridges. The sputtering engine jostled and groaned, and I began to fear shelling might’ve weakened the spans.

There wasn’t a tree to be seen anywhere on what had been a forested mountain. At several junctions, we could see for miles across a wasteland covered with churned-up earth and rock, blown-out stumps and branches, and quagmires filled with black water.

We’d been warned about these mires. Bodies tended to sink and remain inside them. It wasn’t good to get this kind of water or mud near your body or even your boots.

From this point on, my memories play out only in gray tones. Boulders fallen from where they’d clung for thousands of years. Bare-chested men struggle in the rain with long steel bars, leveraging them off points too near the track. Filthy French soldiers sitting by latrine tents and stone-fortified bunkers, stare at us passively as we look out through our window at them. Is it us on display or them?

Many more crosses than we'd seen before began appearing, sometimes densely packed. I couldn’t imagine how whole bodies could ever fit beneath such a number. Something inside me began telling me not to go any further. Maybe some deep animal instinct a when death's that near. The French soldiers we saw must've felt this way for over three years by then. Most all of us had already heard that in the Vosges, thousands of men died in just a single day’s fighting. But we hadn't known what this really meant until our very guts rebelled right then.

As I stepped off the mountain train, First Sergeant Akers almost ran right into me. He shoved me out of the way, setting my teeth on edge, then barking, "Move! MOVE! MOVE!"

From dawn to sunset for the next three days, Akers ran us ragged through tactics and maneuvers. He was no longer the prim Southern gentleman. To me, he was only an evil man who’d forced me execute someone and the fake manners and decorum he’d first exhibited were meaningless. They say war changes people, and I can confirm it, but Akers just went from bad to much worse, screaming obscenities and bullying soldiers like we were the lowest scum on earth.

One morning, he shoved Andy out of formation and onto the ground for having a boot untied and began kicking him in the ribs and the head. The rest of us stood there at attention watching. What could we do? I despised him.

***

On June 14, 1918, we were sent into French trenches for the first time. They were dug zigzagged so that if a shell hit and buried several fellows, the blast wouldn’t spread. This was because so many died through suffocation trying to dig out after explosions.

What more can I say about everything going to hell? It was very dark days as we entered heavy combat. As soon as we were nearby those Huns, the shelling began day and night for four entire days.

When I felt the first burst, I dove down just to escape the noise. Huge clumps of dirt and mud landed on my shoulders and back, and I panicked I'd get buried. I sincerely wished I’d be blown to bits instead of buried. If you're blown up, you just bleed out and die. But if you're buried, you’ve go much slower, maybe screaming but nobody can hear you.

There’d be a short pause, and you’d think you could look up, and then it’d start over. I wasn’t the only one so scared I crawled through horse piss and hid beneath dead bodies.

After this first shelling, Akers didn’t give us a moment’s rest but organized us for patrols and short raids. The Army didn’t have small squads then, and we went in platoons of about thirty or forty to “probe” the enemy’s defenses. All this activity really meant was we were to go see who got shot first. Mind you, I was still only seventeen years old, and I promptly got the shakes. My habit of taking out Wylie’s insignia pin from my jacket pocket and rubbing it with my thumb deepened in earnest then. I’d shove it back in as soon as I felt I could move, so as not to lose it. His pin became a precious piece for me somehow, this memento of a man whose life I’d helped to end.

Out along Vieil Armand, a mountain nicknamed “Man-Eater,” we suddenly came under heavy fire, and nobody could even identify its direction. Rounds rained from everywhere, and I dropped down flat on the ground for a very long time. I was pushing my face deeper in the dirt listening to them whizzing, getting lower, higher, moving right left, for a good twenty minutes.

I was amazed when it let up. It seemed they had us dead to rights but then they just packed it in and moved elsewhere. For a long while, none of us would move. Finally, Paul and I got up into a crouch, and lifted our rifles, aiming in all directions.

What did we think we’d even shoot at?

I shouted out but couldn’t locate Andy. Then I came on him lying near a fence post with his eyes closed. I thought he was resting or scared or playing until I saw a little trickle of blood from his ear. It’s odd how my mind wouldn’t understand what was right in front of me.

Someone standing nearby said he was dead, which didn’t seem right to me, and I demanded proof. I was simply positive he’d been knocked out. A person, especially a young person like him, shouldn’t just suddenly give up the ghost. But a corpsman soon ran up, took out his bayonet and held it under Andy’s nose, then put his hand on his neck and his ear to his chest. He got up and shook his head.

Again, I felt a terrible sting of emotion but didn’t let it show. I was teaching myself not to feel. This was the way a man behaved in my day. Perhaps not much has changed.

Akers marched up, looked at Andy’s corpse, and told us bury him quick where he fell because we had to move. This is how Andy became just another cross.

Paul and I wrote a note to his mother in Iowa that night knowing Akers would never do right by him.

We wanted to explain how her only son had gone out, but how could we? These German attackers were entirely invisible to us – just a bunch of bullets coming from nowhere and everywhere. I could only figure enough to say Andy died doing his duty with courage and ran forward to fight the enemy.

Where was forward? I couldn’t have told her if I tried. The war itself suddenly held no meaning at all to me. But I was stuck deep inside it.