[The Insignia Pin is an original allegorical fable intended for our times that I’m offering to you in weekly-serial form.

The Insignia Pin is an epistolary novel - composed as though the characters themselves are writing it.

This is Part Five. Please read Part One through Four to follow this weekly serial post… and thank you for sharing with others.

Please note: The Insignia Pin is rated PG-13 for coarse language, drugs, war violence, and teen sexuality.]

Frank, 1969

When they took me down to the train station, Mother wore all black and hardly spoke. I was sixteen years old and only knew she was disappointed in me. I did feel a little guilty but also resolved in the stubborn way of teenage boys.

Several times while waiting to board, I said, "Mom, don't worry." She didn’t respond. I tried to look delighted and confident when the train pulled in. It was an awkward situation, and I shook Henry’s hand enthusiastically and kissed Pearl on the cheek.

"Keep your head down," said Henry.

"We love you, Frank," said Pearl. "Come home safe."

Mother burst into tears when I hugged her, and I nearly had to wrestle with her to get her to let go. From the window, I waved, but only Henry and Pearl waved back. Life moves ever forward, I suppose. This memory of my mother is still so sad for me more than fifty years later.

The ride was long and smooth, and I slept most of the way. I started Army life like a fish to water and got paid for the first time during basic training in Rockford, Illinois. Right off, I sent Mother twenty dollars. I suppose I had a lot to prove to her.

A week or so passed, and I got a note back that was loving but short. She was fine, and store business was improving some. Henry and Pearl were going to start raising chickens. Pearl was showing more, and Mother looked forward to being a grandmother. She sent continual prayers for my safety and protection. Not one word about the money, but she didn't return it either.

From Rockford, our group joined with Eleventh Infantry for training through the late spring and summer of 1917 at Fort Oglethorpe, Georgia. We played war games in high heat, drenching humidity, and lots of mud. Otherwise, we dug and filled up ditches. We found this pastime terribly monotonous and wondered what the significance to real battle would be of digging a hole and filling it.

After Fort Oglethorpe, we were sent off to Camp Logan, Texas. This place was jammed with men - just about all of them bigger and older than me. I continued sending money home, but the ten dollars I held back began taking me in the wrong direction. I was going out to local taverns with my new comrades, and when I was in uniform, nobody asked about my age.

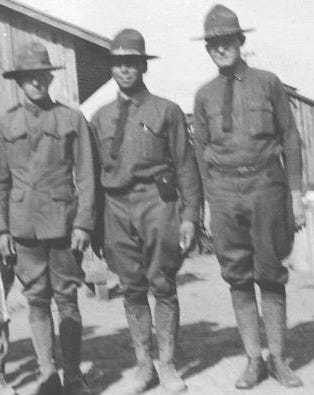

We'd often be hungover, and we had a sergeant glad to make us pay for our sins. Sergeant Wilfred Akers stood over six feet tall without a stitch of fat. I never saw him with a seam uncreased or a shoe scuffed. He fancied himself a Southern gentleman, very strait-laced, and an absolute tea-totaler.

During training, he’d continually ask if you were “man enough” to do this or that. I was a strong kid but small, of course, and I acted somewhat cocky. This didn’t sit well with Sergeant Akers. He suspected I had a God-fearing mother, and he saw me as falling away from my upbringing.

Akers took it as his personal mission to settle me into obedient soldiering. This started off during advanced infantry training when he volunteered me to test the new Thompson submachine gun. I pulled the trigger on a full magazine but couldn’t hold that gun still no matter how hard I bore down. This was amusing, but it was a big mistake to laugh about it in front of Sergeant Akers. He jumped towards me like an angry bear, dressing me up and down as a "miscreant." He accused me of ridiculing a privilege he’d given me and said he’d court martial me for insubordination if I pushed things one more inch.

From there, his negative impression of me only worsened. During one inspection he whispered, “One thing I’m planning while you're still in my Army, Private McCaffrey, is wiping that Jayhawker grin off of your face.”

About a week later, Akers called me to his tent to say he’d volunteered me for “a hanging detail.” I thought this was some kind of military jargon and didn’t ask for clarification. Then the corporal took me aside to say I'd better be packed and waiting for a train to San Antonio by four o’clock that afternoon with six other men.

It wasn’t until we pulled away from the station that I learned Akers had sent me to assist in the hanging of military criminals. I became frozen with horror – here was a duty no soldier would ever volunteer to do. I’m certain every other man with me felt the same.

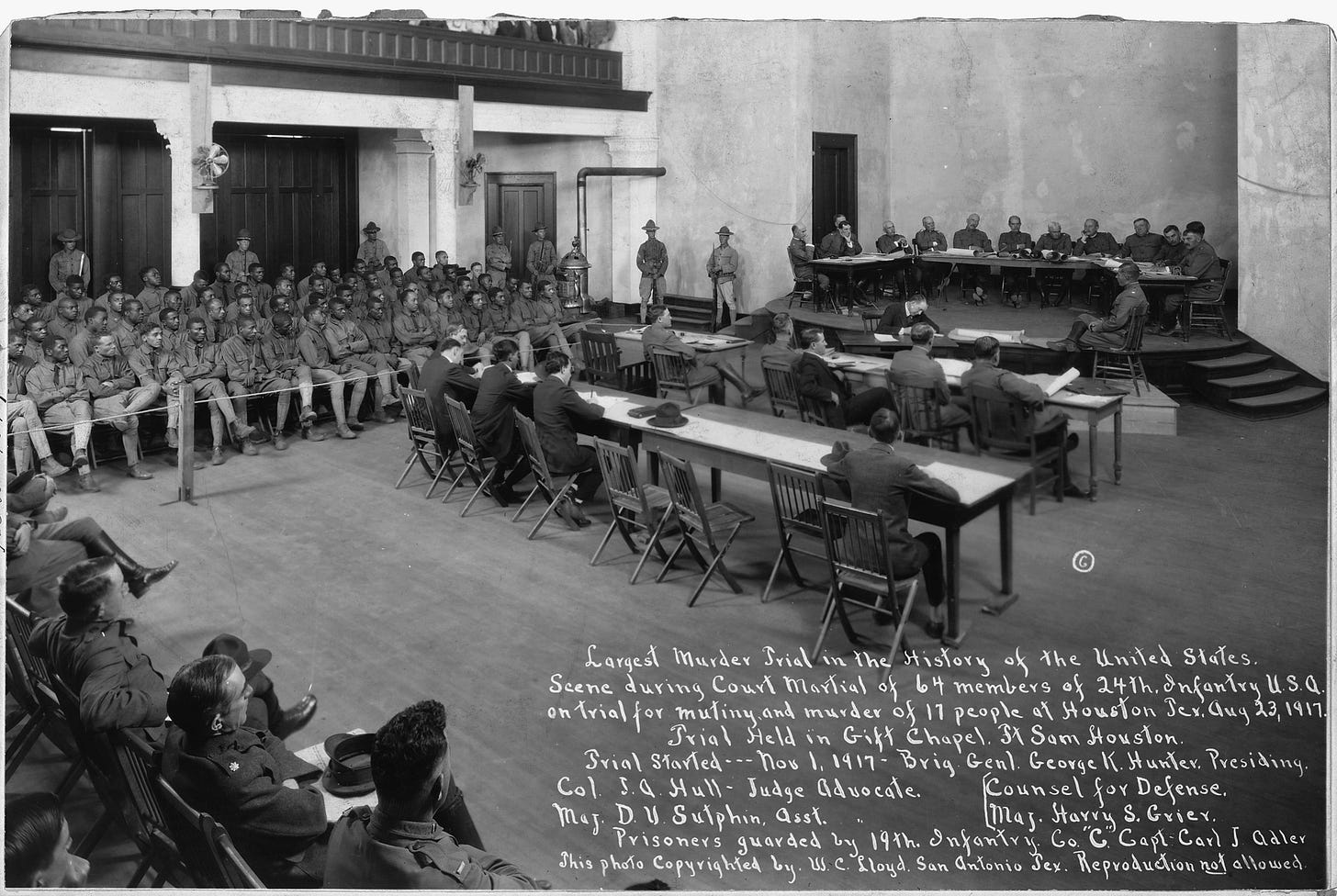

We pulled into Fort Sam Houston and reported to the adjutant for Major Ely at El Paso District Headquarters. He briefed us as to how the Negro Twenty-Fourth Brigade, assigned to guard construction projects at Camp Logan, had mutinied in Houston some months prior. Local citizens were killed, including several white men and police officers. In the largest trial in U.S. history, thirteen of the sixty-four indicted Negro Brigade soldiers were sentenced to hang.

I recalled Mother’s stories about Negro lynching from Ida Wells and asked to speak to the adjutant privately. As soon as he closed his door, I objected to being involved in executions on religious and moral grounds.

“Objection noted,” he answered in a lazy tone, and then he put on a stare. “And say, soldier, you're awful young to be objecting to anything, so I'm going to cut you some slack by letting you in on a secret. These orders are entirely lawful. If you fail to carry them out, I’ll have you placed in manacles and solitary confinement in the stockade until Satan puts on ice skates.”

Then he dismissed me with a wave of his hand.

I couldn’t believe my misfortune. I had to find some other way. Chaplain Bowman was a thin, meek fellow no more than a few years older than me who had a desk set up in the hallway outside the Fort chapel. He listened and then told me he’d already had many questions from other men about the Lord’s First Commandment.

Looking back, I see the ridiculousness of my situation. I’d signed up to be a soldier without realizing I’d no grounds for objecting to orders to kill people.

Bowman said the real reason our units had been sent to hang these Negros was because Major Ely wanted to stay popular with his own men. Sergeant Akers was doing him a favor.

As I got more emphatic, Chaplain Bowman became more resigned. He finally told me I’d be better off accepting that the execution would go forward, and there was nothing I could do about being involved short of going to military prison.

To be without a choice in life and death matters had never crossed my young mind. I wondered aloud, how had I every gotten myself into such a fix? I think he mistook my question to be about what had happened that led to my predicament.

He said when construction began on Camp Logan a year or so earlier, there was abject hatred for the colored man in nearby Houston, especially from the police. Many white people were dead set against having armed Negros stationed near their city. The local Negros knew their place, sitting in the back of streetcars, saying “yassuh” and staying out of the way of white folks in their own ramshackle neighborhoods. They’d never be so stupid as to wear uniforms and put on airs before a white man.

These Negroes from Twenty-Fourth Brigade were a different breed. Years ago, they were known as the Buffalo Soldiers. They had strict discipline, strong camaraderie, and wouldn’t kowtow to anybody, not even a white man.

For these reasons, Fort Logan white officers tried to keep them out of Houston entirely by spreading rumors among them as to how Texas was a lynching state. But the Negro soldiers got stir-crazy and began griping about wanting their liberty like anybody else. They were eventually allowed to go into town.

One hot afternoon, a respectable local Negress called Mrs. Travers was ironing her maid dress in her underwear inside her own home when two Houston policemen named Sparks and Daniels barged in looking for players who’d run off from a crapshoot. Mrs. Travers said she knew nothing about it and made the mistake of asking what did they mean charging into her home in front of her five children? Sparks and Daniels didn’t appreciate her talkback one bit, and they dragged her outside half-clothed.

A Negro soldier named Edwards from the Twenty-Fourth was walking by and spotted these white officers manhandling a near-naked black woman. He went over to ask if they could please give her some clothes, and Sparks and Daniels instead pistol-whipped and arrested him.

Then, on the same afternoon, Corporal Baltimore, a Negro in charge of Twenty-Fourth’s Military Police, stopped at the jail to ask about Edwards. He was instead beaten down and shot but somehow managed to escape. Houston police then chased him and beat him worse, not caring a fig that he was wounded while they did so.

Rumors soon flew back at Camp Logan that Corporal Baltimore might've been murdered and that a white mob was marching out from town to settle things with the black troopers. This is how it came about that these Negro soldiers at Camp Logan stole into their supply tents and loaded their rifles. They then headed into Houston to find Sparks and Daniels, and by the time the violence ended, twenty people lay dead.

Chaplain Bowman said I’d only just missed scores of Negro soldiers in court at one time. Then he looked me in the eye and told me no white person ever did get arrested, and of course, I took his meaning. He was just as troubled morally with it all as I was.

He told me it would be one of these Negro military convicts I’d be taking to the gallows built near a place called Salado Creek.

“But Frank,” he cautioned me, “you must realize the Lord will not hold you responsible for actions you’re being commanded to undertake by a senior officer.”

How would he know what the Lord would or would not hold me accountable for? I told him I did not find this reassuring. It seemed to me that to be a party to unjust killing in any way was no less a sin whether you were ordered to do so or not. Chaplain Bowman made it clear again that my choice was to do my duty or to be locked up or perhaps even taken before a firing squad.

I was but seventeen years old by then. After thinking and praying more than I'd ever done in my life, I felt I had to do what I was told. Were I to go to prison or be shot in dishonor, it would kill my mother and perhaps even shut down the future for Henry and Pearl when word got back home.

I had to obey.

With enormous reluctance, I reported to the stockade where the prisoners were being held, and my assignee was pointed out to me by the desk sergeant. He was a tall, very black Negro who stared directly at me from behind iron bars. His hands and legs were manacled loosely, so he could stand and reach a hand through the bars. I shook it.

“You the young man going to keep me from trouble?” he asked.

I said I was.

“My name is Private Wylie Breckinridge from Boley, Oklahoma.”

I felt uncertain how to act or what to say. He must have noticed.

“Don’t you worry now, Private McCaffrey. We hear there’s still a chance we'll end up going to France with all you boys.”

“Well, I hope you’re right,” I answered him. The desk sergeant glared at me and shook his head.

All that afternoon, there were last-minute pleas and briefings filed by military defense lawyers toward staying the executions. We guards waited along with the condemned to learn the final outcome. Many people came and went, and I was allowed a break to go outside for a few minutes. I watched dark clouds move over the moon before a chilly drizzle began.

By two a.m., it was pitch dark, and a few prisoners dozed, but most others still played cards, unable to sleep. Chaplain Bowman then came by with several Negro ministers. It had fallen on these preachers to tell the convicted that lawyerly tactics hadn’t worked out, and they’d be hung at first light.

Shivers ran down my spine as I realized I’d be following my orders to completion.

Most of the Negro soldiers were understandably shocked by the news. They rose from their cots, running to the bars and begging the clergymen to get them put before a firing squad instead. They pleaded as to how they wanted to die like men and in a dignified manner. Many had been soldiers for some years, and this was all they asked. Their faces come back to my mind to this day – and I still hear their desperate voices never rising above a whisper.

How strange to plead for one’s life in a whisper. Private Breckinridge came up to the bars and waved me over. I leaned in, and he spoke very softly, “If I was to run and you was to shoot me, Private McCaffrey, I’d tell the Lord forgive you.”

His request confirmed for me my deep sense of sin. I couldn’t even meet his eyes, let alone answer.

About then, Corporal Baltimore stepped up, a Negro leader who had a natural authority. He pursed his lips and shook his head, and Private Breckinridge went quiet. Others sat back down on their cots. After that, they just waited and watched us.

Private Breckinridge watched me. I tried not to notice, although I was supposed to keep my eye on him. He’d nod a little if I looked, and I knew his eyes were still begging me.

Dawn came too quickly, and then, trucks and wagons, doctors and more guards. We loaded everybody up and headed out. I was now officially Private Breckenridge’s "conductor," and I sat next to him.

“My poor mother,” he wept ever so quietly.

Here was a man begging me to shoot him, and I thought of my mother and what she'd make of this situation. I had to shake away my own tears.

“S’okay,” he finally said as I moved in to check his cuffs and leg manacles. “You a soldier and got to do your duty. I wish we’d gone together to France.”

Soon the trucks pulled alongside a sleepy river, and we started unloading. We brought the Negroes marching in formation before the gallows. I helped Breckinridge up the staircase behind his comrades and sat him down, pulling the folded canvas bag off the back of his chair as he leaned back. As instructed, I opened it up and lowered it over his head, trying hard not to think about anything at all.

“Private McCaffrey, my Twenty Fourth insignia pin,” his voice quavered a bit, muffled by the bag, and I paused. “The quartermaster has it in my effects.”

“Yes.”

“I’d be much obliged if you’d take it with you.”

I felt confused by his request and couldn’t take his hood back off. I pretended to lean down to adjust it.

“What for, Private?”

“Take it with you when you go, sir,” he muttered just loud enough for me to here. “Keep it with you, and if you can, please bring it to my mother in Boley someday.”

I told him that I would try to do this if I could. How could I not agree to a dying man’s wish?

The noose lowered down from above, and I eased it over his head. I can never forget this moment. It haunts me to this day. The medical officer came by and tugged it hard before he tightened it around Wylie’s neck.

At this point, Corporal Baltimore was allowed to stand up before his chair. He thanked all the guards for not beating his men or “treating us like murderers.” He then sat back down to finish being prepared by his guard in the same fashion I’d done.

Once every man was situated, each conductor was told to climb off the scaffolds and form ranks. Major Ely appeared and addressed the hooded Negro convicts where they sat while the rest of us gazed at all of them. None were even able to see their own executioners. One by one, he read each man’s convictions and the sentence of death by hanging.

When he finished, he told them that when he called them to attention they should stand up as “the soldiers they once were.” At that moment, every one of us became rigid and silent for several seconds.

“Attention!” shouted Ely, and the thirteen men jumped up in perfect unison before their chairs. His arm went down, the traps were sprung, and all thirteen men flew downward at once.

Afterwards, two other men helped me place Private Breckinridge’s body in a casket, and we dug all thirteen graves side by side. Chaplain Bowman and the Negro preachers oversaw their Christian burials only a few feet away from where we’d hung them. We took apart the gallows quickly, so there’d be no trace of the awful work we’d done.

I did ask Major Ely about Private Breckinridge's insignia pin, and he had no objections and told the quartermaster to pass it over to me.

For three nights thereafter, I was the sentinel to Wylie Breckinridge’s fresh grave, standing in the darkness, listening to the river flow, hearing his voice begging me to shoot him, seeing myself lowering the hood and noose over his head again and again.

While others slept, I’d pull out his insignia pin from my pocket. A round “collar disc” with the number “24” in the center, and two crossed rifles beneath. I’d already developed a nervous habit of holding it between my thumb and forefinger and rubbing it.

When I got off duty, I’d stroll by myself alongside Salado Creek. I began acting very solitary whenever anybody took a stab at trying to talk to me.

I’d lost sight of myself as a good person, you see. I figure this sin put me at arm's length from the rest of the world for the rest of my life.