The Insignia Pin, Part 2

Reflections from the Burning House

[The Insignia Pin is an original allegorical fable intended for our times that I’m offering to you in weekly-serial form.

What you’re reading is not the final version, and I’m hoping you might collaborate some with me through your comments, questions, and reactions.

The Insignia Pin is an epistolary novel - composed as though the characters themselves are writing it.

This is Part Two. Please read Part One to follow this weekly serial post… and thank you for sharing with others.

The Insignia Pin is rated PG-13 for language, drugs, war violence, and teen sexuality.]

Frank, 1969

In midwinter of 1910, Bitter Bill lost our property deed to a gambler named Kelly Daniels. For the little it was worth, this deed got passed to him free and clear as a wedding present from your great-grandpa Alex Stewart. But your grandpa laid it right out on the table as a wager – which I saw him do with my own eyes. He lost to Daniels’ straight with a full house, aces high. Yes, my father lost my boyhood home by a full house.

Daniels had his own enforcers among the very people my father had welcomed into the back room of his shop, and he knew he had to sign the deed over or else. Mother was off visiting the sick with some ladies’ church group. The card game broke up, and I followed him and watched him hurry to pack a suitcase and then rush out our back door. Up strolled a local whore named Ivy Long, and they caught a train to Des Moines that very afternoon.

Your grandpa Bitter Bill McCaffrey ran off dragging Grandma Mary’s wedding silverware in his big bag. He took away our home and the only thing worth any money in it. Even with me trailing his every move, he didn’t have a glance or a goodbye for me, his son, and I was shouting at him and grabbing at his coat too. He never was any real father.

I called out to Mother what happened the moment she walked in. She became beside herself with anxiety and tried to think what to do. Early next morning, she borrowed a neighbor’s mule and got herself over to the county seat to try to fight the deed transfer. But the whole swindle was done. The clerk had his hands greased.

Suddenly all we had to our names was a few pieces of beat-up furniture, clothes needing stitching and mending, a couple dollars in coins, and a bag of worn-out cobbler’s tools. Then, about two days later, Kelly Daniels comes climbing up our stairs with key in hand. He starts walking right in all the while we’re eating boiled potatoes, and Mother shoots up and tries to push the door closed. I run up and help push too.

Daniels pokes his cane through and swings at the two of us like we’re a couple of stray dogs. He pushes inside and barges right past us. Then he strolls around while Mother grabs her carving knife from the kitchen. He laughs and says she shouldn't worry. He’s got no use for our place, and then he asks did she want to rent it, so we could stay living there.

Can you imagine paying rent for what you owned free and clear just a few days before? And where would ever she get any real money? Back then, a woman usually depended completely on the man.

Well, she saw how everything was and after Daniels left, we went down to Reilly’s Reclamation. The cobbler tools got us ten dollars, not near enough. We were put out of our own home by the Sheriff the next Monday, and you could see he didn’t care for the job. Mother wept on his shoulder and he near cried too.

I did see your grandpa just one more time – in a pinewood casket coming to Chillicothe by train in my early twenties. I was very unwell at the time, staring down at his ugly, shriveled face. I decided all he’d done to hurt people made him look that way, and I vowed never to become anything like him. Be careful about the promises you make to yourself.

***

After we’d lost so much, some town folks began looking down their noses at us. Mother took on scrubbing floors at night in several stores and also at the post office. In this way, we found our way to a small room at Mrs. Albert’s Boarding House.

I was often left to my own most days while she slept. Roaming around, I could sometimes feel folks judging me as Bill McCaffrey’s "bad stock." That’s how people thought about such things. When I got caught red-handed filching meat from Taylor’s Grocery, Mother’s disappointment made me feel so ashamed, especially because Taylor’s was one of the stores she scrubbed.

Rather than have me locked up in reform school, Mr. Taylor thought I could work off my thievery. I did well enough, and after a month or so, he started giving me a dollar a week.

When she could, Mother still got her Winslow’s syrup to help her sleep through the days. She became very melancholic and was always tired. She tried giving the goop to me too, but I told her flat out I wanted no more and thought it terrible stuff.

I guess she considered what I said because she told me she would quit the habit. But a day or two after she gave it up, her belly started hurting, and she passed out with chills. I ran to find Doc Evanhurst, and he gave her bromide and quinine, but this made her all strange and sluggish.

The very same night, she began calling out loudly in scripture like she’d been taken by the Holy Spirit. Psalm eighty-six, “Bow down your ear, O Lord, hear me: for I am poor and needy.”

I felt sure she was dying, and I’d end up an abandoned orphan. But she got color in her cheeks by morning and ate a little bread. She told me the Lord had rescued her from the Devil.

From there, we had just enough to live on for a time. Then, one wintry day, the plating on the kerosene stove at Taylor’s got so overheated and red, he couldn’t get it cooled down before we had to shutter up. So he asked me to crack open the back window before I left, but like many a boy, I forgot all about it and went about my business. The fumes built up, and the heat from the stove ignited. A fire broke out, and Mr. Taylor and his family barely got out alive. Fire trucks were not invented yet, and the horses ran off with the old pump rig before anybody could douse it. Taylor’s store burned down to the ground.

I heard the alarms and commotion and ran over there to find his wife standing next to him, holding all these little kids, sobbing, and watching it burn. That’s about when I remembered what he’d asked me to do. Mr. Taylor never said one word more to me. A small-town storeowner had no insurance or this sort of thing, so they lost everything.

About then, I began feeling like nothing but bad luck and trouble.

Our situation got more pitiful. Mother had lost a store to scrub, but she talked the postmaster into letting her scrub twice a week. I felt like her having to work so hard was my doing. Spring came on, and we started going out and picking rhubarb and strawberries along easements between farms which she’d can into jam.

I’d get to feeling so guilty seeing her red knuckles and nicked up fingers, I could only feel any better by chasing down wagons coming to market and holding up Mason jars and shouting out prices. Mother made a good jam. I started trying to help more by taking odd jobs like carting coal, selling newspapers, or cleaning stables. I'd often miss school and take any work I could find for just pennies or food.

I wasn’t yet ten years old, and there were no laws against poor boys working. She needed my help, but she wanted me educated even more. Whenever Principal Sabrowsky alerted her I hadn’t shown up to school, she’d chase me around our tiny parlor, swinging a broom and screaming I’d be a “worthless, sponging idler” like my father. I understood her to be distraught, but this scolding stung me.

We didn’t have much family nearby to turn to. As I mentioned, my older sister, your Aunt Pearl, was twenty-one by then, and she and her husband, Henry Babbitt, had moved out to Kansas a few years earlier.

Pearl eloped when she was seventeen. I was still a pup then, and no doubt our terrible father had much to do with it, although I never knew the dark particulars. I didn’t grow up so much with her as without her because Pearl would stay with her girlfriends’ families for weeks at a time. I think she often felt guilty about not being around for me, but I never held it against her.

In those days, people would rather fix a garment than throw it away, so Mother came upon the idea of taking in sewing. This was never going to be rich trade in Chillicothe, but she got a little to stitch here and there, which she did all by hand. Even so, we kept losing ground, and Mrs. Albert finally told us she wasn’t running a charity, and we’d have to move out. After a time, we couldn’t even make the weekly rent at the seedy Union Hotel.

A farmer named Mr. Milton came upon us one night wrapped up in wet blankets and pitiful, sitting in the rain in front of a chunk of coal smoldering in a tin can. That’s about the most miserable we ever were, and near starving too, but he led us back to his stable, where he and his wife brought out slices of ham, a loaf of bread, and butter.

It was our first decent food in weeks, and Mother quoted Luke to him and his wife: “They will pour into your lap a good measure, pressed down, shaken together, and running over.” Mrs. Milton got all moved to tears and told Pastor Edmonds about us. For a time we took up sweeping and scrubbing at Assembly of God Church for a night’s rest sleeping on cushions on the pews.

Good Christians back then wouldn’t blame you for being poor as though it was your fault. After all, Jesus loved the poor and was poor himself. Nobody in that church knew anybody rich anyway except for people we'd read about in the papers – the Rockefellers, Vanderbilts, J.P. Morgan, and the like.

With the pastor’s encouragement, poor folks not much better off than us came forward with a bit of cash. Then Pearl somehow wrote to the address we had at the church and told Mother very firmly that if we were going to get back on our feet, she and Henry felt it best for us to be living with them. I know Mother was very grateful to those church people for helping us get train tickets for our move to Iola, Kansas.

***

Pearl and Henry lived six miles east in LaHarpe and struggled to run a tiny grocery not too different than Taylor’s. After we arrived, we used what little cash we had left to rent a room for a few weeks. Right away, Mother started putting up notices about her sewing business that Henry helped her get printed.

All this served to change our fortunes. She’d become a very good embroiderer, and some pleased old biddy offered to loan her a real sewing machine. This device was a true Godsend because it helped her cater to more well-to-do ladies at city rates.

I took up hawking again, this time the Iola Tribune, morning and evening editions. I also came up with a dip bait for flathead catfish that I used from atop the steel bridge over the Neosho River. I always had the knack, you know, and there were many occasions when I got four or five fish and sold them. I also wasn’t above mucking manure for "a nickel a stall, dime a sty" at a farm near town. Even as a young boy, I always worked as much as I could. Like I say, I didn’t want to turn out anything like my own father.

It's true I left Chillicothe prior to completing the sixth grade, and your mother sometimes liked to note this was all the education I ever received. I didn't have much formal schooling, but I've done correspondence courses up through basic algebra and also studied philosophy. I’m a self-educated man and owe nothing to nobody.

We began to have real food on the table and to pay our way. Mother bought me my first pair of lace-up boots about then from the Sears and Roebuck. I’d always run around mostly barefoot as my father wouldn’t make me shoes often enough to keep up with my growing feet.

Can you imagine a cobbler’s son with no shoes? When I got this first pair of real boots, I thought myself the happiest lad far or near.

Things were looking up, and just prior to turning thirteen, Mother let me join up with a wheat threshing crew in western Kansas to work from early June until just after July Fourth. I got so excited about the idea, I could hardly speak. This was real man’s work, and I thought it a great adventure.

The trains came through Iola purposely slow so as to make it easy for us to hop the flatbeds. Watching the town move off into the distance gave me a great yearning to see more of the world. I was at an age when a boy thinks this way. Our home was always so flat and even, stretching on forever – with endless golden fields of wheat swaying in the wind as the train sailed by. But I’d gotten so used to the sameness of it all, and I didn't sense its beauty like I do now. I only longed to see real mountains and the ocean and maybe the Great Pyramids.

I was made the ‘flunky’ on this crew of twenty-five men and one woman who did the cooking. Our first day out, the boss went over particulars of the separator, a contraption pulled behind a Hart Parr steam engine, and we were warned as to the speed and attention involved. Two days later, I stood right next to a young man screaming and looking down on the deck at severed fingers from his right hand. In my boyish awkwardness, I remember I'd enjoyed playing cribbage with him and how hard it was going to be for me to ask him to play again. When he came back from the doctor with a huge bandage, I became so terribly squeamish about his wounds, I could hardly look at him anymore.

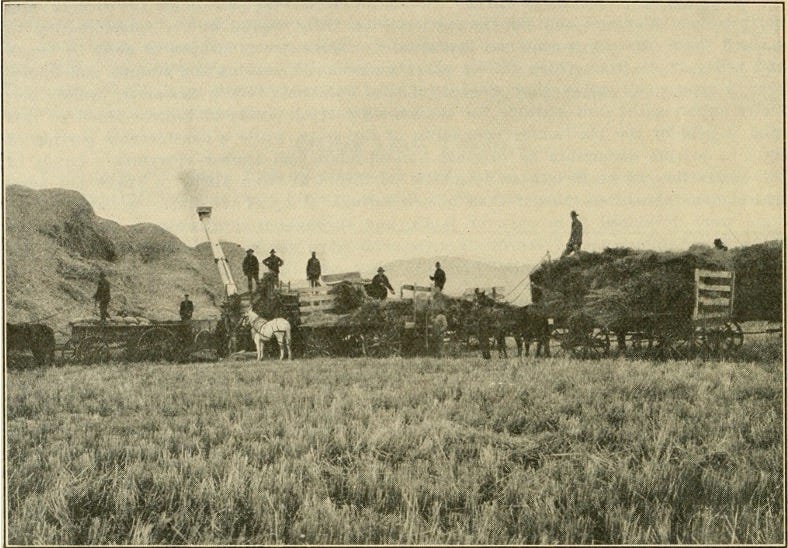

We toiled sunup to sundown during harvest and were hauled to different spots across the Kansas fields. Line after line of wagons driven by farmer’s wives pulled up, piled high with sheathes of wheat. Threshermen hoisted and pitched the shocks into our separator, which shot grain from the shaft into a bin, spraying chaff along a conveyor and blasting it out through a stovepipe onto a growing mountain of straw. I never lost my fascination for it all and slept like the dead every night I was gone.

There was a hierarchy among the boys, and you had to show you were big enough to take whatever anybody might dish out. Being small, they saw me as an easy target, but they soon learned different. I'd already been in many scrapes, and I guess I had a kind of violent streak from all I went through at the hands of your grandpa. Sometimes they’d have to pull me off some crying kid much bigger than me. The men took to calling me “Little Hellfire,” and I guess I liked it some because the other boys all backed up from picking on me, and I’d shown I could take care of myself.

The flunky’s job was to pitch the straw for the fireman to feed into the steam engine boiler. Coal was too expensive for most farmers, but there was always lots of straw. It burned hotter, so the temperature gauge would sometimes spike, and the fireman might yell out a warning to slow down on the straw. Now, if the driver skedaddled off his rig, everyone else would jump in a panic and run in all directions. But the poor fireman had to stay and whirl those valves fast as lightening to try to leak off a huge plume of pressured steam to keep the whole rig from blowing up. I was very grateful to be a flunky and not a fireman.

By the end of a day, wagonloads of separated grain started lining up at the local mill to be spilled into silos or ground right away and bagged into forty-pound sacks. With harvest in, our crew moved from farm to farm, hoisting these bags onto wagons or onto cars on tracks behind the mill. As wheat harvest season closed up, I came home dragging along a bag as part of my pay. Mother started into baking, and this would always make me feel proud. We'd have buttery popovers with eggs at breakfast for weeks. The flour our crew made couldn’t have been any fresher.

By age fifteen, I'd become a wiry little fellow, able to lift my own weight above my head. I had a job at Iola Electric Park then, loading and working the roller coaster. There was swimming, paddleboats, dancing, and sports and exhibitions. I guess several girls showed a passing interest in me, but I was much too shy. Besides, I couldn’t afford to take a girl around.

In August of 1915, I asked my boss if I could apprentice as Park electrician, but he thought me too young. I never did go back to school, but I always liked to learn. To someday go off to college like my sons would never have entered my imagination. I did enjoy reading about Tom Swift and his motorcycle in the books Pearl and Henry loaned to me.

Caff, 1970

And who am I writing to anyway? Myself? Mrs. Fitch says I should write to somebody in my journal like me in the future. That'd be cool because the only person who’s ever going to see this book is me. Otherwise, I’ll burn it before I’ll show it to anybody.

Okay, so I'm calling you Future Dude and you are me someday a long time from now.

I want to write seriously about falling to peer pressure because no adults seem to understand why it ever happens. We had a cop come to class and talk about the dangers of weed. Jarv and I were both stoned to the bone which was too funny when you think about it.

That cop was talking about peer pressure and telling all the kids not to fall for it. Well it sure is not easy.

He’s lighting up something supposed to smell like weed without it being weed in this little pie tin. Like we don’t already know what it smells like!

Anyways peer pressure is exactly how I started tripping out on acid.

This whole situation with acid began right after we smoked four bowls of Jarv’s crummy weed in a homemade pipe underneath the slide at Eton Park. It’d be better to make rope out of that shit because it gives me a headache.

Well we go to Village Green head shop to get pipes and bongs and papers. Man I bought this solid hash pipe from the fox at the counter who wears this see-through muslin shirt and she didn't even card me. I figured she was into me.

“Damn” she told me when I was staring “put your eyeballs back in your head.”

That girl’s hellacool. She knew I only bought that pipe to have a good look at her boobs. Jarv said maybe just save my money because Whole Earth Catalog has a topless babe on p. 71 if you really want to study the female form. How the hell would he even know that much about a book I own and haven’t even looked at??

Anyways so we’re at Eton Park and Jarv is explaining how he invented his weed pipe so he wouldn’t get hassled for being under 15 and trying to buy stuff over at Village Green.

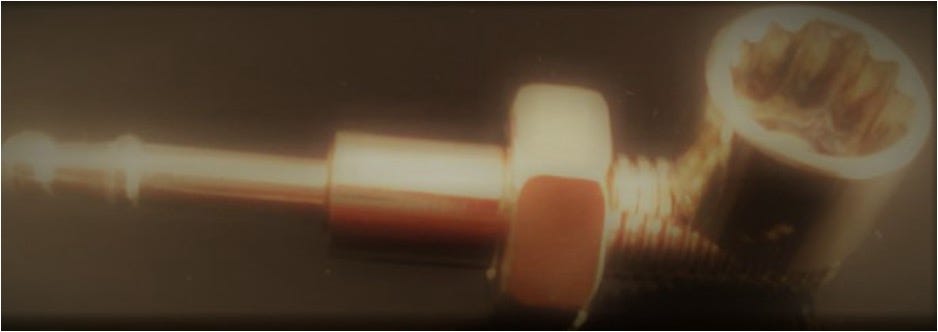

I’m writing instructions from what he said because it’s so ridiculous:

Ride your bike over to Maskill’s Hardware on Adams.

Go to plumbing in Aisle 6.

Grab a filtered garden hose end piece. I’m saying what it’s called from the shelf label. It's a kind of metal tube with a little screen inside.

Grab a right-angle brass adapter. It's right next to the end piece thing.

Slice off a piece of clear plastic tubing with the razor utility knife hanging by a string by the link chain and rope.

Crotch all the pieces like you’re tucking your shirt in.

Don’t feel bad! Mr. Maskill makes shitloads of money. He’ll be at the register reading his paper and won't even look up.

You got your parts, now just screw the garden hose end piece into the right angle adapter and scrunch the clear tubing on the other end.

Fill up the round little bowl inside the garden hose end piece with some bomb ganja. The little screen inside is your filter.

I ripped parts for mine while Mr. Maskill was sound asleep with the Detroit News on top of his head. My dad says the News is a shit paper. He likes the Free Press.

Future Dude! I shotgunned some high-grade shiba from my homemade pipe and choked out Jarv. It was the BOMB! I watched smoke blasting through the clear tube and - blam! - he's all in convulsions on his bed.

Well we were smoking weed at Eton Park with my new pipe when Neil drove up and said he’d score us some Boone’s Farm Tyrolian wine if we left him and Dorene alone the whole night. I said no problem and Jarv could sleep over. We got really ripped and walked to my house. Then I accidentally put on the un-blipped version of ‘Kick Out the Jams’ by MC5. Not even on the 45 you know. Mom was home and taking a nap.

"Kick Out the Jams, motherfuckers!" right??

Mom barges into my room without knocking.

“Did I just really hear what I heard??”

It smelled like booze and ganja too!

Damn, I had to think fast.

I told her we were burning patchouli incense and asked how’d she like it?

Then I explained we were listening to a song about truck driving, and how truckers sometimes jam their gears going down hills.

Then I looked at her, all blinking and asking why’s she so upset anyway?

She said she couldn’t even repeat what she thought she heard in this horrible rock music playing much too loud.

I said “Huh? You mean ‘kick out the jams, brother truckers?’”

She looked at me and she was squinting.

Jarv's jaw’s hanging wide open.

Mom was looking right at me with my eyes at half-mast. The thing was - hers were too!

And - whew - she believed me! She just shook her head and said “Well, turn it down!” Then she shut the door and walked away.

That’s the best thing about Valium I told Jarv. “Mother’s Little Helper” that’s what it is.

Damn, I didn’t finish what I was going to say about this peer pressure thing and tripping out.

Now I gotta go take out the trash.