[The Insignia Pin is an original allegorical fable intended for our times that I’m offering to you in weekly-serial form. What you’ll read is not in its final version, so I’m hoping you might collaborate some with me through your comments, questions, and reactions. The Insignia Pin is an epistolary novel - composed as though the characters themselves are writing it. It opens in 1969 with a grandfather, Frank McCaffrey, who is in poor health and has started a memoir addressed to his estranged adult son, Samuel, in a last ditch effort to restore their relationship. He has much to explain. It then shifts back and forth with the journal entries of John McCaffrey, more often called “Caff,” who is Samuel’s 14-year-old son and Frank’s grandson. Caff is writing in 1970 after Frank has died. As this is my first post of this series, I’ll want to know whether my readers out there will feel interested in continuing to follow weekly posts of this sort. Please let me know. One last thing: The Insignia Pin is rated PG-13 for language, drugs, war violence, and teen sexuality.]

The Insignia Pin

Frank, 1969

Samuel, I can’t handwrite legible due to my stroke eighteen months ago, which you wouldn’t know about. I'm sitting here in the kitchen with my magnifier light over an IBM Selectric Pete Travers, our building manager, loaned me.

Today’s my sixty-ninth birthday, and it’s been two years since I got sober. Ethel, my AA sponsor, says she’ll quit me unless I make amends with you. I told her we don’t communicate, but she says I’ve got to figure some way anyway. I’ll send this your way, maybe you’ll take an interest or not, but I’ll keep a copy on hand too.

Doctors say I might stroke again and lose my memory, so I want to tell you all you never knew. Since I shot off the pistol, there’s not been one word from you. I had only mentioned you not knowing how to use a carving knife, and I don’t recollect all this about wrestling with Oscar or knocking little John down. Oscar said you and Sophie call little John “Caff” which as you know was my own nickname growing up.

Yes, I shot off my Colt pistol out my own kitchen window later that night, but no harm done, not even to trees in the backyard, and it’s my pistol. It’s a valuable war relic you’d no right to take. As to shooting car tires, I never did anything of the sort.

Sophie said then no further contact "for the time being." And now it’s stretched ten years such that I’ll die without my grandsons ever knowing me. But I’m done whining and will start with what I need to say.

When you yourself had a bit too much Jim Beam under your belt you said you wished I’d done more than walk a mail route. I sat there and took it, and I know what I heard. So this was the beginning of how things went south on that Thanksgiving Day.

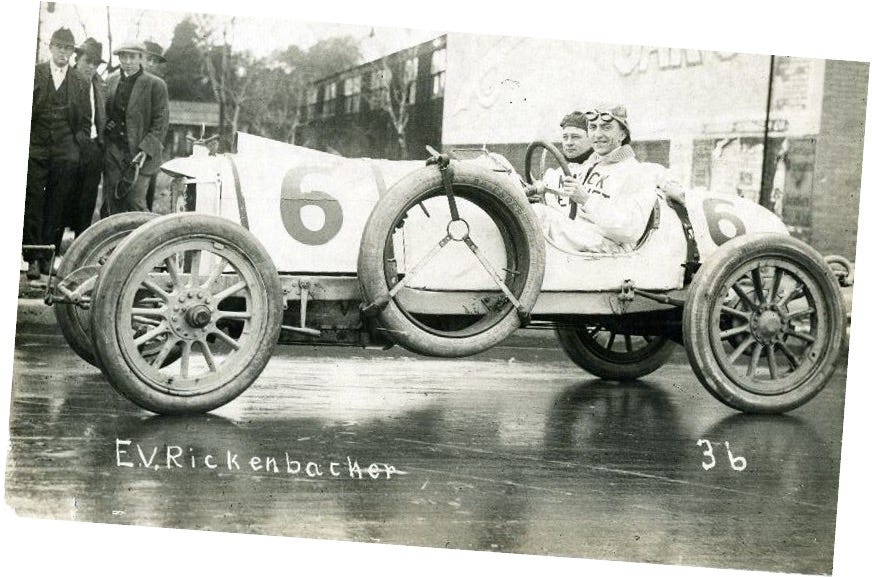

I’ll begin my story by saying, for your information, that I was almost an airmail pilot. You may be surprised with all you don’t know about me. This was at the time I worked a Bridgeford boring rig at Rickenbacker Motors over on Michigan, which was Eddie Rickenbacker’s company while he was still an auto racer. He’d put his winnings into making cars after the Great War. I was there after we had left Oklahoma for Detroit.

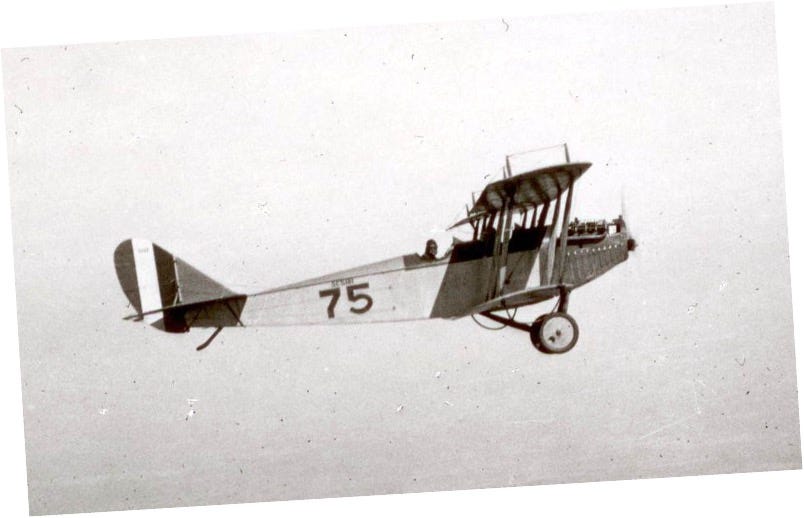

Most of us were impressed with “Rick” whenever he dropped by, and he knew how to keep people on his side. He was quite a charmer. I won an employee raffle to go up in a Larsen monoplane along with him. He drove us out to Haggerty field himself on a Saturday, and we met up with his wife Adelaide and a couple of her lady friends.

Rick was still a national hero then, and he put your own father down into the cockpit of that plane that day just to show me around. You had to use your whole body - feet on the rudder control and brakes, and both hands on the wheel. This was real flying.

I moved to the back, he took over in the pilot seat, and his man got her started. He pulled the choke back, shoved the throttle, and we sailed down a grass runway into the wind. The engine was so loud you couldn’t hear your own voice, and the windows had no glass, so we had to wear goggles.

Very few people had ever even been up in the sky in those days. It was a huge change in perspective. What a treat it was to see farther than I could ever imagine. Rick banked us so hard over the Detroit River that Adelaide’s lady friend started screaming, thinking we’d fall out. As for me, I never laughed so hard. I was a country boy, and this flying business just tickled me. I’d never known such thrills.

After we landed, Rick told me there’d be a need for airmail pilots. He was encouraging me right then and there to take it up, and this was something I hoped I'd end up doing. But I never felt the need to tell you or Oscar. What father talks about dreams that never work out to his sons?

Nonetheless, I’m saying the hell with you for your crack about me walking a route.

I did get to solo on the stick of an old Curtis Jenny several times. There wasn’t much more to do for a flying license, but you had to show the authorities you could do it safely. I was just about to have a man come up with me and do so, but then Ford and Studebaker got worried about Rickenbacker four-wheel brakes being better than theirs. Those connivers bought loads of newsprint about our cars being accident-prone. Our sales hit the skids, and Rick proved fickle and shifted all his attention to car-planes. What a ridiculous notion.

This was all in 1926. He shut down his car business and hightailed out of Detroit and left workers like me in Dutch. So now I was out on the dole, and I’d walk past his and Adelaide’s place along East Jefferson, thinking I might run into them and give him what for. We’d all looked up to the man, and this was our mistake because he left us high and dry.

There was no Walter Reuther or United Auto Workers or sit-down strikes; all that stuff was still years away. There was no unemployment pay, and losing your job meant you and yours would go hungry. Ford shut down Model T production, and many fellows came out alongside me trying to figure what to do.

Understand your mother and I were newly married with your older brother, and you weren’t born yet. She didn’t want to leave Detroit after just coming from Oklahoma. She was adamant about it, and to keep bread on the table, I got involved in some illegal activities. You might recall a big tiff between me and her at a point when you were about five years old where she rode me down as a criminal. Well, she never complained about the money, and I do have much more to say about it all.

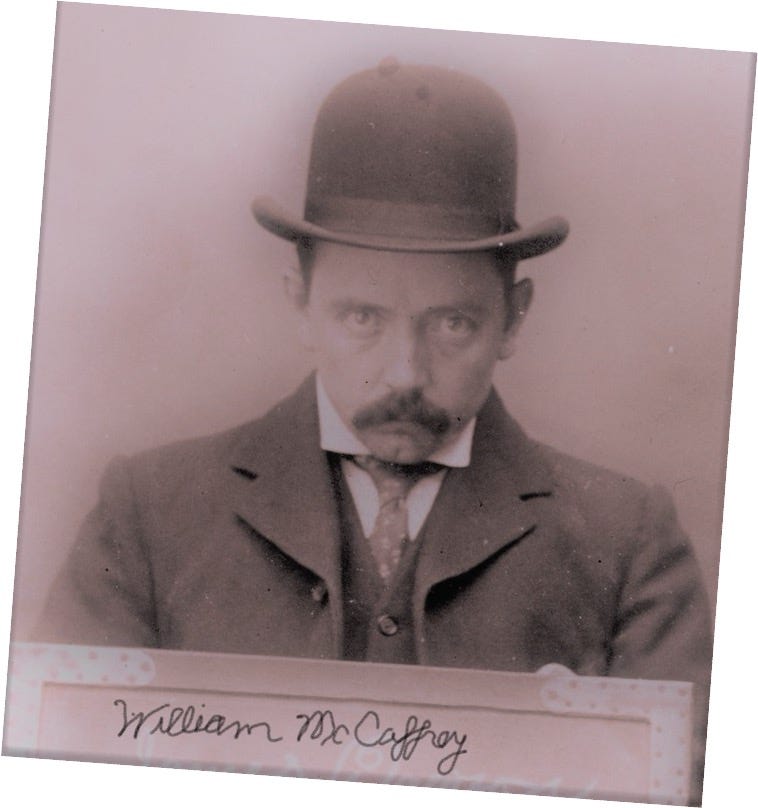

When I was a kid, I had no time to play toy soldiers or climb trees like you two boys but spent my days rushing growlers from Mr. Wolff’s Saloon in central Chillicothe to your grandpa’s shoe repair on Eleventh. Our family lived above the shop - Mother (your grandma Mary), him, and me. Being quite a bit older, Aunt Pearl had already married by the time I was six years old.

After school, I'd have to start my fetching for my father. Growlers were little buckets of beer about ten cents a fill, and I’d hang them by the handles on two sticks slung over my shoulders. You never knew your grandpa William McCaffrey, which I assure you is all for the best. He’d down a growler in one long draw like one of these Coca Cola commercials you see today. Any extra he’d sell for a nickel over his cost to his lowlife friends living around us.

I had to grow up hard because he was always too lazy or drunk to work and saw any child of his as paying their way. Pearl had already been through enough with him and found a way out. But I was left behind to walk around miles after my school day or on weekends hawking beer. If he could have got me away from school entirely, he’d have done it, but the district man came around here and there to check for truant kids. To me, school was just a place I could sleep anyway. After school and for hours more, I’d better not spill and bring either the beer or ten cents for whatever’s missing, or he’d pull out this thick piece of shoe leather and have at it with me.

All I knew then about what a grown man was, a father figure, was him. Somebody to scare you, push you around, yell at you, and hit you in the head. I see him leaning against an oak tree in an alley back then, draining his little buckets, dripping foam down his scraggly beard, maybe talking to some grimy hobo and trying to get his nickel. He’s forever tipping up his beat-up bowler on his head like some kind of tough guy. Maybe if he got drunk enough, he’d try a little cobbling. But being a cobbler was always mostly for show, and he was more generally looking for a con or a hustle or a wager to make.

He’d make me smoke a nickel cigar with him sometimes. I’d get faint-headed, and he’d laugh at me like I was his entertainment. I am about eight years old in these memories. When he got really lit, we’d have to stay out of his way. Mother and I’d wedge ourselves beneath the kitchen table when we heard him stumbling up the stairs.

Grandma Mary was a very slight-built woman with pale skin and a huge head of hair bundled up. She often carried a fearful, downtrodden look. He’d drag my mother out from under the table and slug her in the belly or the nose like she was a man. She’d slap at him like a Raggedy Ann doll, swinging her arms and screaming. Then I’d pop up, jump on his back, and try to box his ears. He’d fling us both off him and come at her again. I’d jump on this back again. This happened night after night, and being a kid, I never understood it, but I also didn’t know any different. Sure, I’d see how some of my little friends had it better, but I couldn’t sort out why they did, and we didn’t.

I once saw my father kick a fence post until it broke in half, and he happened to be sober on that occasion. He had no end of anger and deviousness inside him. He started hosting games of chance as another money-making scheme, so that the backroom of the shop got filled up with the scum of the earth, drinking and smoking or chewing tobacco. There’s nothing like neighbors who’ll spit tobacco juice on the floor of your own family’s business. He seemed to like having these kind of men around. I think it helped him feel like he was better than them.

During those terrible days, Grandma Mary got herself addicted to Mrs. Winslow's Syrup, which some people called ‘Mother's Little Helper.’ I guess me too, but not nearly like her. She would tell me when she fed this goop to me that she was keeping my teeth from hurting. Looking back, I figure she was keeping me settled down to stay out of his way.

This was even more true for her. Whenever she could shake a few coins from him, my mother would be drinking this goop morning and night. There was no regulation back then, and that syrup was actually mixed with morphine and alcohol, if I’m not mistaken. Getting it by the tablespoon is my earliest memory of the attraction of liquid pain relief – from that Mrs. Winslow’s syrup.

Caff, 1970

Caff, 1970

I’m in a bad mood and must be very bored. How bored I am can be seen in me writing in this blank book Arnie gave me for my last birthday the crummiest ever.

It seems dumb but it's all I've got to do right now.

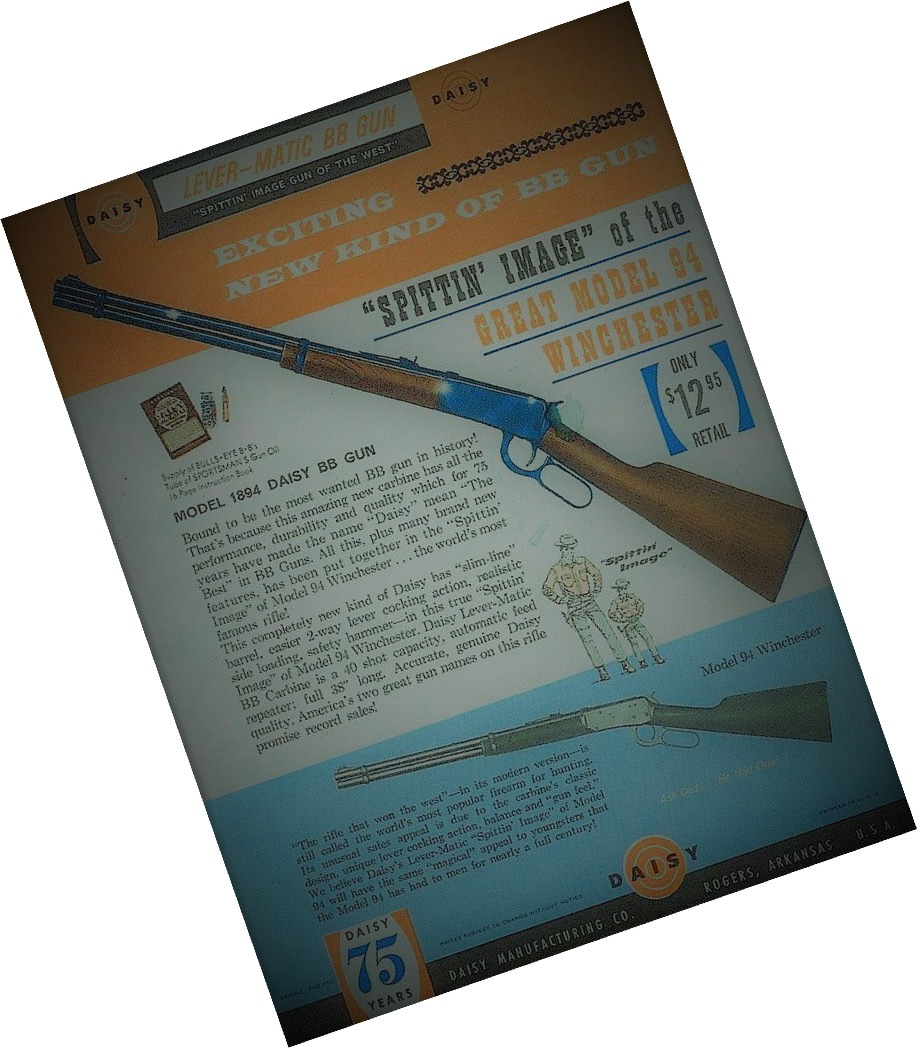

I wanted a Daisy Winchester BB gun, but Dad and Mom are totally opposed to guns and this Vietnam war is why I can’t have one. I’m old enough for sure so that's totally bogue.

They gave me a desktop radio but I already got two transistors. I'm not just going to sit here and listen to the radio.

Compare this birthday to last year when I got Beatles’ White Album AND went to Cedar Point.

Mom and Dad gave me a huge book called Whole Earth Catalog that won't even fit my bookshelf. It has all this far-out stuff for sale but I don't got any money so what’s the point?

Dad grounded me for calling Arnie a little prick because he won’t loan me any money. He’s been in a crap mood almost a whole year ever since Grandpa Frank and his brother my Uncle Oscar died just six months apart from each other.

I always thought Dad didn’t care about Grandpa Frank because of him being a drunk and not being around but he got super upset when he heard he passed. Arnie and I never even seen him cry before. And Dad had no use for Oscar after him doing some criminal stuff with his clothing business but he was really down after he died too.

Anyways Dad hasn’t had time for me and Arnie and so we never do anything together.

Mrs. Fitch was the one said I should try writing because I’m pretty fair at it. She told me Randolph Falcon Scott kept a journal on his way to the South Pole and there's nothing pussy about it.

Well, she didn’t say it that way!

Anyway, diary’s for girls and a journal’s for boys. I’m keeping this one hid behind the board on my bedroom wall that has bathroom pipes in it.

Ugh! I hate being grounded.

I want to go to Jarv Vallant’s right NOW because it’s never boring there!

Mr. Vallant taught me to play “Fold Some Prism Blues” by Johny Cash on his Silvertone guitar and Jarv’s mom sometimes makes fried corn mush for dinner.

A few weeks ago when Jarv’s mom went to the grocery his sister Dorene and her boyfriend Neil started screwing in her bedroom. Man we walked right in, me and Jarv. Dorene screamed and chased us out and she was holding only a blanket in front of her naked body.

Totally bomb!

Dorene's not half bad but I’ll never tell Jarv. Anyways we take off and Neil can’t catch us bare foot. Then Mr. Vallant wakes up in his lazy boy all red-eyed and plastered! He drinks Goebels all day long on Saturdays.

Dorene comes tearing back through the front door and into the front room and her dad starts squinting at his daughter standing there without a stitch on only that blanket. Then Neil comes running in behind her trying to catch me and Jarv.

Oh man shit hit the fan!

Mr. Vallant got up and stumbled off to his bedroom and then Neil said “uh oh,” and he ran and jumped right through the front screen door - he didn’t even bother to open it!

Neil takes off down the street and Mr. Vallant comes hopping behind him through the ripped-out screen, falls right on his face, gets up, and starts shooting a real pistol up into the air!

Blam-blam!

All the while he’s screaming “Son a bitch! Son a bitch!”

I mean Jarv’s household is totally nuts!

Neighbors called cops and they even came!

They cuffed Mr. Vallant and threw him in jail overnight for drunk and disorderly. That’s about when Mrs. Vallant got home from the grocery and she’d only been gone a half hour.

Damn, I never seen my mom or any woman get so mad. Her face was lit up like Christmas!

Fucking A, you know? Never boring over there.

WAIT - I gotta go to dinner.

Yech, pot roast. Stringy.

Okay - Jarv was born in Tennessee so he’s got a Southern accent. I sure am glad I don’t have an accent because it makes you hard to understand.

I never know what the hell he says the first time around and he’ll repeat and repeat until I’m just sitting there staring at him.

Then he’ll say something like “Horse pucky.”

He says that’s Southern talk for nonsense. Then he tugs me along to show me whatever he’s talking about - like how he stashed a lid of primo Jamaican behind the left brake light of Mr. Vallant’s old Pontiac in the garage. That car doesn’t even run so who’d know?

I forgot to say Mr. Vallant is a fully qualified arch-welder for Charley’s Auto at Normandy and Coolidge.

I thought Jarv kept saying ‘fully-qualified fart smeller.’

That’s just my sense of humor.

We walk to Charley’s sometimes and there are zillions of cars there. After I get my license I’m saving up for a ‘68 Shelby GT500KR Cobra because that's what Astronaut Scott Carpenter drives.

Cobra jet, four-barrel carb, and Ram Air Induction. KR, man - King of the Road!!

I live in Detroit Michigan. Right on!

The Motor City.

Keep it up!