Sometime in 1963 when I was seven years old, I underwent a pediatric intravenous urogram, or IVU, due to my chronic bedwetting. By then, I already knew myself as a source of shame and dismay for my mother, who had to wash my sheets nearly daily, and worried about my potential unmanliness. Retrospectively, she referred to this childhood problem as my “weak bladder.”

The only advance explanation I received about this procedure was that the “doctors are going to try to figure out why you wet the bed.” I sure didn’t know myself, and I wished I didn’t do so because it meant I was considerably less of a “big boy.” I couldn’t be trusted to go on overnight Cub Scout outings or sleepovers with friends.

Thus, I was a willing patient and not particularly scared going in. If the doctors could fix me, I’d be glad. The room at the hospital outpatient clinic was very cold, likely sterile, and my mom was not allowed to come inside. My dad was at work, and my sisters were probably with a babysitter. I’d been brought in by a male nurse - I don’t think he was a doctor - and he told me to take all my clothes off and put on a hospital gown he handed to me. He then left me alone in the room.

Soon, a female nurse came in with a huge styrofoam cup. She seemed very friendly and invited me to sit down in a chair. She asked if I liked Vernors soda, a popular beverage originating in nearby Detroit. I’m sure I said something like, “sort of,” because Vernors was very carbonated, and the ginger ingredients burned my nose. I didn’t really like it.

But I agreed to try to drink the Vernors she’d brought me. As I did so, I wanted to less and less. The nurse kept prodding me; “You need to drink this all up, Davy.” This was a hell of a lot of Vernors. The typical amount required for the hydration phase of a pediatric IVU protocol was one to two liters. The point was to distend the child’s bladder to its fullest in order to obtain an x-ray with contrast.

She kept refilling the styrofoam cup, and I drank - and drank - and started to worry and tell her I couldn’t drink anymore. She continued to insist I must finish all the Vernors. I got panicky and wanted to see my mom.

“It’s okay,” the nurse reassured me, “She’s still here. But she’s just going to tell you to drink all this Vernors too.”

I suspected she was right, and this was long before any time when a nurse sitting with a panicky little boy would resort to going to get his mom. She’d won; I was forced to comply and drink Vernors until I drowned in the stuff.

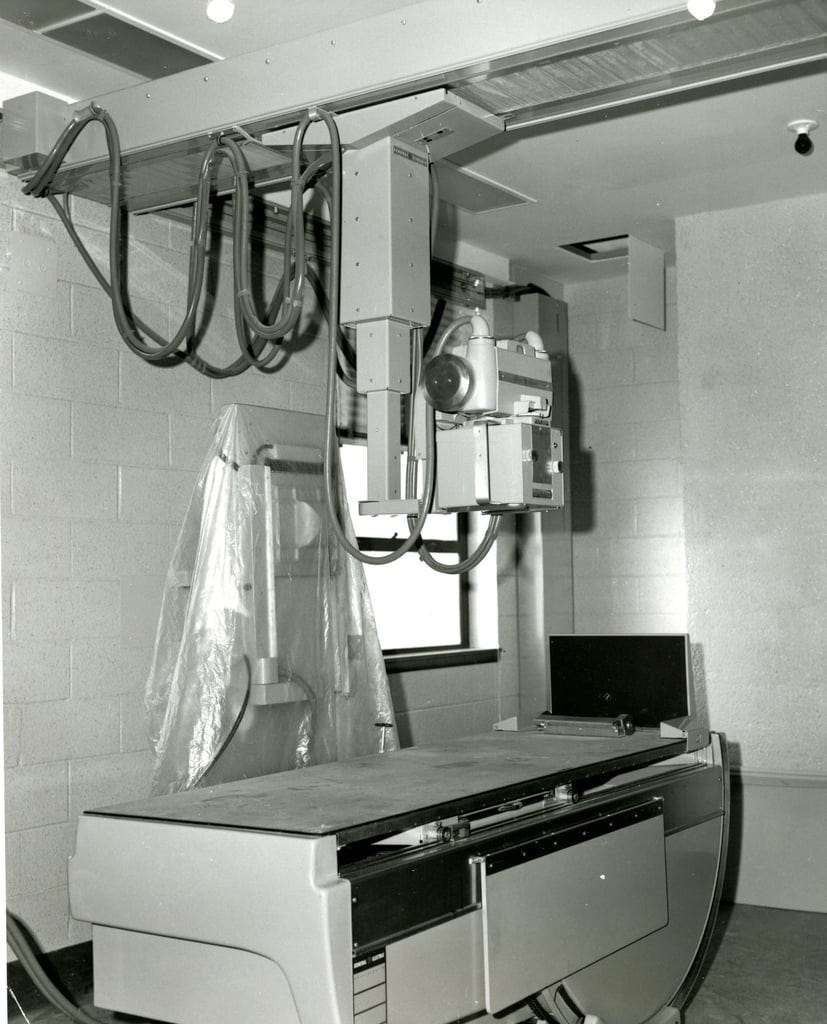

I finally finished, but I had to pee. The nurse then told me I “must” hold my pee until they’d finished. She then instructed me to climb onto the x-ray platform and lie down. She told me someone would be coming in soon and left the room.

I really had to pee, but I had to hold it. This was my mantra at that moment. Don’t pee, don’t wet your pants. Well, gown.

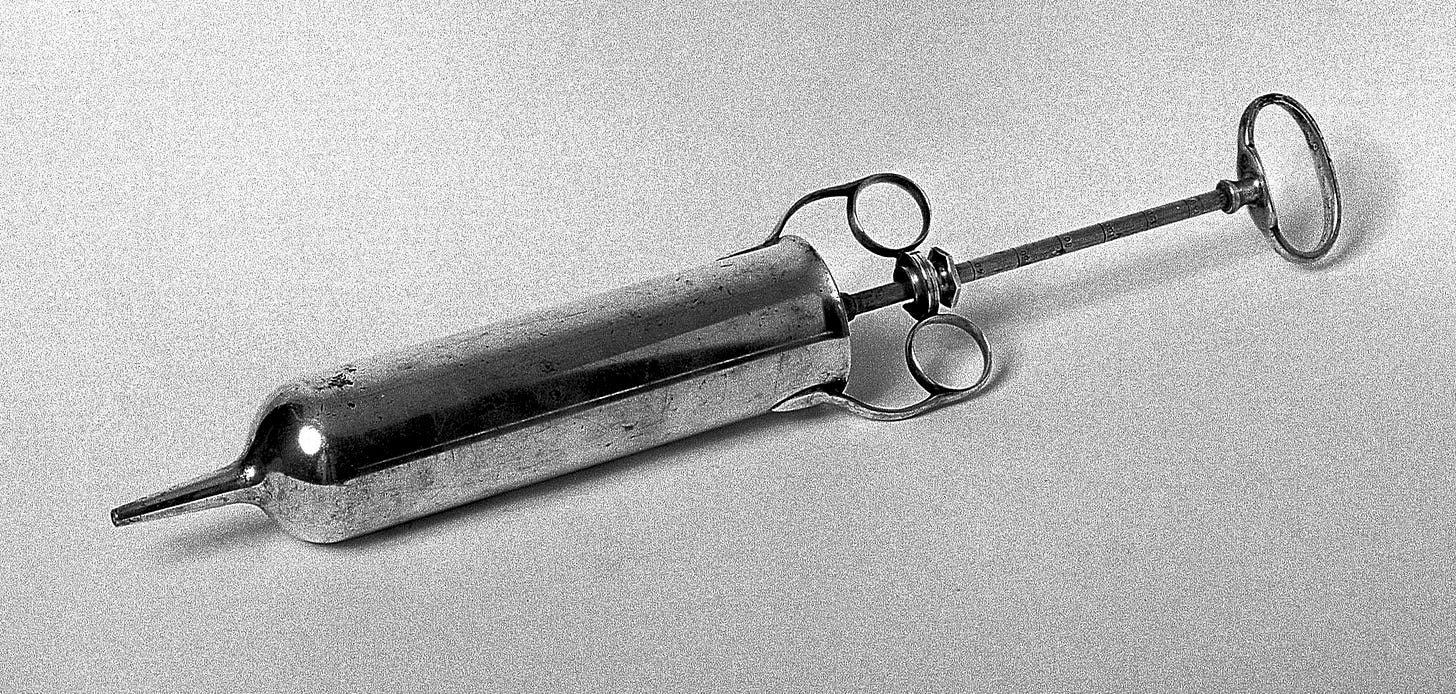

From up on top of the platform, I spotted a metal cart next to another x-ray platform with the largest syringe I could ever imagine. It had three round plunger handles on it. I remember thinking how sorry I felt for whoever the hospital patient was who would have to have a shot like that. After all, no one had said anything about a shot. And I’d been told even though we were going to the hospital, I wouldn’t be staying in it.

The male nurse returned. He wasn’t unkind. “I’ll bet you have to pee, so let’s hurry and get this all done,” he smiled. I said okay, and as I lay there, he tugged out a kind of sliding board from beneath the platform and told me to rest my arm on it. He then began using medical tape to restrain my arm to the board. He glanced across the room at the tray.

It was about then that I started to realize this big shot was for me. Not only that, but I’d be getting the shot into the inside of my arm, an experience I’d never had before. I started panicking again, and the male nurse noticed.

“Davy, it’s going to be okay. But it’d be best if you close your eyes before I give you this injection.”

I squeezed my eyes shut, and my heart rate shot up as I grimaced. These days, I’d say I was definitely in a fight-flight state physiologically and emotionally, but all I knew then was that I might die from this one shot.

The prick did hurt a lot, and I began to tear up.

“Almost done,” he said.

Big boys don’t cry - this was doctrine in raising boys then, of course. I dutifully pushed my tears back hard because I didn’t want this male nurse to see me cry. After all, I already had this “weak bladder” thing and felt ashamed - why add to it?

Nowadays, we know suppression of tears disrupts the release of endorphins and other proactive, stress-mitigating physiological responses. We also know pressuring boys not to cry pushes them deeper into a toxic trope of the stoic, emotionless man who won’t feel intensely. That is, until he’s enraged, violent, self-destructive, or depressively withdrawn. But this kind of understanding of the traumatic, negative effects of emotional suppression on the wellbeing of boys and men wasn’t in anybody’s minds when I was seven and had my IVU.

Nor do we live in a time of any greater enlightenment now. I’ll pause to note that I strongly suspect the effects of toxic “manosphere” bullshit (excuse my French) is a major factor behind 57 percent of registered U.S. male voters under age 30 voting for the current president, and along with it, his regime’s support for the “male ideals” of Christian Nationalism. These young men are being reached and exploited in droves by twisted, thoroughly broken, and willfully ignorant male influencers and podcasters via their loneliness, resentment, pain, and terrible confusion about what it means to “be a man.” That’s not a new problem.

I want to help in taking that phenomenon on. For my next several posts, I want to surface for you and yours some explanations as well as what we might do about “all that’s gone horribly wrong” - and continues to go wrong - in the dysfunctional socialization, resulting confusion, and violent chaos of boys and men.

I fervently believe current male emotional problems are a leading-edge barrier to any social progress in dealing effectively with the global metacrisis of rising autocracy, climate collapse and species extinction denial, misogyny and the oppression of women, racism and intolerance, economic inequality, and technological disruption among so many other interdependent issues. Left unaddressed, insidious and historically-resistant “male emotional problems” are going to lead us to another world war well before we can do anything meaningful about the rest of these major problems.

It’s far too big a task for a blog, I admit, but I’ll suggest references, resources, and solutions for those wanting more, and leave the key points for those of you wanting only the cliff notes.

Turning back to how my bedwetting was finally explained to my seven year old self, well, I was told the findings of the IVU showed that there was nothing “physical” wrong with me. Therefore, the pediatrician told Mom, my bedwetting was primarily a psychological issue. Perhaps my resentful rivalry as the oldest with two newly-arrived younger sisters could explain its onset. My wet bed sheets were diaper-substitutes for wanting to be her baby again. My “over-involvement” with a “neurotic” mother and my relationship with an ambivalent and competitive father might be the culprits behind why I peed the bed at night.

No, no, these were not what mom told me at age seven - but they were some of the crazy explanations she reported being given when I asked her in her elder years. At age seven, she only told me it was “nothing physical,” which meant to me that my bedwetting was my fault. This conclusion was reinforced by the new requirement that I strip my own bed of wet sheets, which I didn’t really mind except feeling it to be an intentional punishment for being such an ongoing disappointment.

Additionally, on rare mornings when my bed remained unsullied, I’d now have responsibility for making it. I don’t think I understood this part, and I acted up. I got spanked rather severely for purposely peeing on the top sheet one day in order to not have to make the bed, but the scolding hurt much more, and I never did it again. Such were the failed devices of a seven-year-old boy trying to avoid a new chore loaded with emotional significance.

We know now that nighttime enuresis results from some combination of making too much urine while you sleep, reduced bladder capacity, and difficulty waking up. It’s got a genetic component, affects about 7 percent of kids worldwide, and is about twice as prevalent among boys as girls after the age of five years. There are medical approaches that can help a lot, and none of them are psychological.

No such explanations existed in my own childhood, and I slept through the newest behavior-mod innovation of an alarm going off on a special wetness sensor sheet. I still recall Mom’s anger at being awoken instead of me to an instant need for a change of sheets in the middle of the night.

This approach was quickly abandoned, and I finally outgrew bedwetting at nine years old.

I can hardly bear to add to the mix how my self-hatred was exacerbated by my thumb-sucking habit at night. I felt even then that I must be some sort of “big baby” but finally “cured” myself by tying my hand to the bedpost for three consecutive nights at age twelve. The first two nights, I awoke with my thumb in my mouth asleep against the bedpost.

The clarity of my memory for the IVU procedure still impresses me. Today, putting a child through such a medical experience would be considered abusive and unethical. The long-abandoned routine intravenous (IVU) protocol of the early 1960s has many elements known to evoke what’s been labeled as Pediatric Medical Traumatic Stress (PMTS), a kind of childhood PTSD. Fortunately, I don’t suffer flashbacks of triple-plunger syringes or coercive nurses making me drink gallons of Vernors and not letting me urinate.

Instead, I carry the wounds of disinformation about what it meant to be a man. The toxic messages of those days are having a resurgence.

The messages are the same now as back then, and I feel them deeply. They involve running face first into a visceral aloneness and emotional scarring, a profound sadness at being a disappointing little boy and the ways in which my natural exuberance and sensitivity could be murdered in a single moment, a sense of unworthiness that became the best explanation for my father’s distance and preferences for excluding me in favor of his solitary activities. There this boy still exists - activated by these grotesque resurgent messages to young men and boys of this generation - still inside me like a ring in a tree trunk, depicting my very young self, head hung down, enraged, forcing himself to stop crying, standing alone in his bedroom, having flung a plastic airplane model at the wall and then stomped it to pieces for not knowing how to make it all by himself.

Age eight years, I think. One year post-IVU.

Make it by yourself and stop crying. That’s the message for boys and men, and the flipside of male privilege - the twin-note doctrine of radical individualism, the roots of American male asshole-ism, selfishness, greed, and “why should I give a shit about you? Or them?”

I entered puberty already knowing I’d never become the “man” I was supposed to be. I didn’t have it in me. Sure, I no longer wet the bed or sucked my thumb, but there was nothing else to support emerging manhood except my very skinny physicality and smooth, un-bristled cheeks. Standing in the kitchen with Mom and Dad at age fifteen, experimenting with “joining in” intellectually about some controversial topic, I unconsciously held my hand in front of my chest while I spoke. In the midst of my own fledgling assertions, Dad suddenly shouted - “David, put your hand down - you look like a faggot!” I overdosed on prescription sedatives I’d bought from friends at school about six months later.

There it is - I’d already drunk the Kool-Aid well before Dad served it. Don’t cross your legs; don’t hold your hand in front of your chest. It’s back in vogue. And by the way, God bless my queer kindred for enduring for generations - and continuing to endure - their own maligning as “repulsive other” on behalf of instilling this kind of self-hatred in hetero-boys like me for their own sensitivity and open-heartedness in the world.

To today’s young men seduced by the newly twisted, thoroughly broken influencers preaching make America into shit again via toxic maleness, I know exactly what it feels like to believe you’ll “never be man enough,” and I also know these guys telling you this crap originate in the “willfully ignorant” crowd. Be careful who you let tell you who you are.

In coming posts, I’m going to expose this ignorance, describe some potential means of opposing and intervening in it, and hopefully, offer in the process some ways for all of us to help boys and men grow into better men.

This touches the core of my heart and the core of the endless vulnerability of the heart and the courage to heal, and to see and to touch into the depths of the wounds, not only in service to self feeling, but to a greater good. So much love for this little boy in this grown man and his advocacy deeply grateful to you and all of your work Dave. 🫀🕊️